Technologies

How to Boost Your Phone Signal for Better Reception This Holiday Season

If you’re traveling for the holidays and struggling with bad reception, these 10 tips can help.

You know that special kind of holiday-travel panic? Your phone’s signal bars just… disappear. One minute you’re following the GPS to your in-laws’, the next your map is frozen, the festive playlist is dead, and you’re stranded in a dead zone. It’s not just an inconvenience; it can be a genuine safety issue.

But before you start cursing your cell carrier, you should know the problem often isn’t the network-it’s your phone being stubborn. It’s probably still clinging for dear life to a weak tower you passed 10 miles ago instead of finding a stronger one right near you. The fix is usually a ridiculously simple trick that takes about five seconds.

Stop accepting bad reception as a fact of life. Whether you have an iPhone or an Android, here are the quick and easy ways to force your phone to find a better signal. Here’s how to do it.

Don’t miss any of our unbiased tech content and lab-based reviews. Add CNET as a preferred Google source on Chrome.

Note: Although software across different iPhone models is relatively the same, Samsung Galaxy, Google Pixel and other Android phones may have different software versions, so certain settings and where they are located might differ depending on device.

For more, check out how you can use Google Maps when you’re offline and how you can maybe fix your internet when it’s down.

To improve your cellphone service, try these steps first

The settings on your phone can help you get better cell service but there are other tricks for improving your reception without even touching your phone’s software.

- Move yourself so that there are no obstructions between your phone and any cell towers outside. That might involve stepping away from metal objects or concrete walls, which both kill reception. Instead, get to a window or go outside if possible.

- Remove your phone case. It doesn’t hurt to remove whatever case you have on your phone, especially if it’s thick, so that the phone’s antenna isn’t blocked by anything and can get a better signal.

- Make sure your phone is charged. Searching for and connecting to a stronger signal drains power, so if your phone battery is already low on charge, you may have a difficult time getting good service.

Always start by turning Airplane mode on and off

Turning your phone’s connection off and then back on is the quickest and easiest way to try and fix your signal woes. If you’re moving around from one location to another, toggling Airplane mode restarts the Wi-Fi, Bluetooth and cellular network modems, which forces them to find the best signal in the area.

Android: Swipe down from the top of your screen — to access the Quick Settings panel — and then tap the Airplane mode icon. Wait for your phone to completely disconnect from its Wi-Fi and cellular connections. It doesn’t happen instantly, so give it a good 15 seconds before you tap on the Airplane mode icon again.

iPhone: On the iPhone, you can access Airplane mode from the Control Center, but that varies depending on which iPhone model you have. On the iPhone X and later, swipe down from the top-right corner to access the Control Center. On older iPhone models, swipe up from the bottom of the screen. Then tap the Airplane mode icon, which will turn orange when it’s enabled. Again, wait up to 15 seconds before turning it off.

If Airplane mode doesn’t work, restart your phone

Our phones are miniature computers, and just like computers, sometimes you can fix issues like network connection by simply restarting them.

Android: Hold down the power button, or the power button and the volume down key (depending on your Android phone), until the on-screen menu shows up, and then tap Restart. If your phone doesn’t offer a restart option, you can simply tap Power Off to shut down your device, and then boot it back up with the power button.

iPhone: On the iPhone X and older models, hold down the sleep/wake button and either one of the volume buttons and then swipe right on the power slider to turn off the device. Wait until it fully turns off, then press down on the sleep/wake button to turn it back on.

Alternatively, you can do a force reset on your iPhone: Press the volume up button, followed by the volume down button and then press and hold the side button. Keep holding it in, after your phone’s screen goes black and until you see the Apple logo appear again.

If your iPhone has a home button, hold down the sleep/wake button until the power slider is displayed and then drag the slider to the right. Once the device is turned off, press and hold the sleep/wake button until you see the Apple logo.

Older phone? Take your SIM card out

Another troubleshooting step that might help is to remove your SIM card, if your phone has one, and then place it back in with the phone turned on. If the SIM card is dirty, clean it. If it has any physical defects, you may need to replace it.

You’ll need a SIM card tool — usually included in your phone’s box — or an unfolded paper clip or sewing needle to get the SIM tray out of your phone.

All phones: Remove the SIM card, check to see if it’s damaged and positioned in the SIM tray correctly, then put it back in your phone.

eSIM: For phones with an eSIM — that is, an embedded electronic SIM in your phone — there’s nothing for you to remove. The best you can do is restart your phone.

Check your carrier settings (and update your software)

Mobile carriers frequently send out carrier settings updates to help improve connectivity for calls, data and messages on their network. Although this feature is available on all iPhone models, it’s not universal on Android, so you might not find carrier settings if you don’t have a supported phone.

iPhone: Carrier updates should just appear, and you can update from the pop-up message that appears. To force your iPhone to check for a carrier settings update, go to Settings > General > About on your phone. If an update is available, you’ll be prompted to install it.

Android: As mentioned before, not all Android phones have carrier settings, so you’ll have to open the Settings app and type in «carrier settings» to find any possible updates. On supported Pixels, go to Settings > Network & internet > Internet, tap the gear next to your carrier name and then tap Carrier settings versions.

Reset your phone’s network settings

Sometimes all you need is a clean slate to fix an annoying connectivity issue. Refreshing your phone’s network settings is one way to do that. But be forewarned, resetting your network settings will also reset any saved Wi-Fi passwords, VPN connections and custom APN settings for those on carriers that require additional setup.

Android: In the Settings app, search for «reset» or more specifically «reset network settings» and tap on the setting. On the Pixel, the setting is called Reset Wi-Fi, mobile & Bluetooth. After you reset your network settings, remember to reconnect your phone to your home and work Wi-Fi networks.

iPhone: Go to Settings > Transfer or Reset iPhone > Reset > Reset Network settings. The next page will warn you that resetting your network settings will reset your settings for Wi-Fi, mobile data and Bluetooth. Tap Reset Network Settings and your phone will restart.

Contact your phone carrier

Sometimes unexpected signal issues can be traced back to problems with your wireless carrier. A cell tower could be down, or the tower’s fiber optic cable could have been cut, causing an outage.

For consistent problems connecting to or staying connected to a cellular or data network, it’s possible your carrier’s coverage doesn’t extend well into your neighborhood.

Other times, a newfound signal issue can be due to a defect with your phone or a SIM card that’s gone bad. Contacting your carrier to begin troubleshooting after you’ve tried these fixes is the next best step to resolving your spotty signal.

If all else fails, try a signal booster to improve cell reception

If after going through all of our troubleshooting steps, including talking to your carrier to go over your options, you’re still struggling to keep a good signal — try a booster. A signal booster receives the same cellular signal your carrier uses, then amplifies it just enough to provide coverage in a room or your entire house.

The big downside here is the cost. Wilson has three different boosters designed for home use, ranging in price from $349 for single room coverage to $999 to cover your entire home. To be clear, we haven’t specifically tested these models. Wilson offers a 30-day, money-back guarantee and a two-year warranty should you have any trouble with its products.

Technologies

Social Media and AI Want Your Attention at All Times. This New Documentary Says That’s Bad

Your Attention Please, a documentary premiering this week at SXSW in Austin, Texas, explores how we live in the attention economy.

«Do you remember the world before cellphones?»

The question comes early in Your Attention Please, a documentary premiering this week at South by Southwest in Austin, Texas. And it hit me harder than I expected. As a 27-year-old tech reporter, I realized I don’t have too many clear memories of life before smartphones. My adolescence unfolded alongside the rise of smartphones, social media, push notifications and the routine of endless scrolling. Like many people my age, I’ve spent most of my life inside the attention economy — without ever really stepping outside it.

That’s the uneasy territory the documentary explores.

CNET was given exclusive early access to the film’s trailer, embedded below.

Exploring how tech shapes our behavior

Director Sara Robin said she originally set out to make something smaller: a documentary about people trying to reclaim their attention by breaking unhealthy phone habits. In an interview with CNET, Robin described the idea as a personal story about focus and self-control in an age of constant distraction.

As Robin interviewed researchers, technologists and families affected by social media and cyberbullying, the film’s scope widened. What started as a question about individual habits quickly became a larger investigation into how modern technology systems are designed to shape human behavior. The story stretches from the rise of social media to the emerging influence of AI.

Along the way, Robin and her collaborators kept hearing the same observation from different corners of the digital world: Social media didn’t just change how people communicate; it quietly rewired what we value. Experiences that were once private or emotional — friendship, affection, belonging — began to acquire numerical equivalents. Followers, likes, comments, views and shares began to be how we saw our own self-worth. In the architecture of social platforms, those numbers function as a kind of social currency.

Trisha Prabhu, a digital-safety advocate and inventor of the anti-cyberbullying technology ReThink, argues that social platforms did more than create new online spaces. She says they fundamentally reshaped how social validation works. The metrics that define popularity often reward attention-seeking behavior and amplify conflict, while genuine connection is now harder to quantify and, therefore, easier to overlook.

Prabhu warns that the same dynamics already driving problems like cyberbullying could accelerate as automated systems become more capable. AI tools can generate abusive messages at scale, produce convincing impersonations or create deepfakes that spread rapidly online. In some cases, the technology may even blur the line between human interaction and machine-generated communication, which could deepen loneliness or encourage harmful behavior.

«There’s AI exacerbating existing harms [like automating cyberbullying], but then I also think that there’s AI creating completely new harms,» Prabhu told CNET. «There are reports of AI tools encouraging users, including minor users, to commit self-harm… Even for the everyday user who’s not experiencing the extreme outcome, I think we have to ask ourselves how much of our time and connection we want spent with an AI tool as opposed to a fellow human being.»

Bringing attention to attention

What struck Robin during filming the documentary was how universal these anxieties felt. Across conversations with families, educators and advocates around the world, the themes were remarkably consistent: overstimulated attention, declining focus in classrooms, rising anxiety among young people and a persistent sense of dread that comes from always being plugged in.

Those shared concerns have helped spark a coordinated moment around the film’s release.

On March 11, more than 25 organizations focused on digital well-being will simultaneously release the trailer for Your Attention Please as part of an initiative called Stand for Their Attention. What began as a small collaboration among five groups quickly grew as word spread through advocacy networks. The coalition now includes organizations such as Common Sense Media, Protect Young Eyes, Mothers Against Media Addiction, the Center for Humane Technology, Smartphone Free Childhood and Scrolling to Death.

The idea behind the synchronized launch is simple: Use the attention surrounding the documentary to highlight the growing movement that’s already working to reshape digital culture.

Many people feel overwhelmed by the scale of the problem, Robin says, but behind the scenes, a widening ecosystem of advocates is experimenting with ways to build healthier digital environments, from redesigning products to changing norms around screen use.

The campaign also arrives at a moment of growing scrutiny around the attention economy. Lawmakers in the US and abroad are increasingly debating how social platforms affect youth mental health and childhood development. Boycotts around AI use are taking off. Researchers are studying how these algorithms and chatbots influence behavior. Individuals are trying to figure out how much technology belongs in everyday life.

What can we do about it?

Despite the weight of those conversations, Robin says the goal of the film isn’t to leave audiences feeling powerless. In fact, the rapid rise of public awareness around AI has made her more optimistic than she was during the early days of social media. The systems shaping digital life, she argues, are built by people, which means they can also be rebuilt.

«We have more power than we think,» Robin said. «And there are a lot of different ways to get involved in this, from changing individual habits to changing the culture in your own family and in your community, designing technology differently, getting engaged in these conversations, all the way to pushing for legislative change.»

The film intentionally avoids presenting a single solution.

Instead, Your Attention Please asks a broader question: What happens when attention, one of the most human parts of our lives, becomes one of the most valuable commodities in the global economy? And perhaps more importantly, what kind of digital world do we want to build next?

Technologies

Today’s NYT Connections: Sports Edition Hints and Answers for March 12, #535

Here are hints and the answers for the NYT Connections: Sports Edition puzzle for March 12, No. 535.

Looking for the most recent regular Connections answers? Click here for today’s Connections hints, as well as our daily answers and hints for The New York Times Mini Crossword, Wordle and Strands puzzles.

Today’s Connections: Sports Edition is a tough one, with some very unusual categories. The blue one is pretty fun, actually. If you’re struggling with today’s puzzle but still want to solve it, read on for hints and the answers.

Connections: Sports Edition is published by The Athletic, the subscription-based sports journalism site owned by The Times. It doesn’t appear in the NYT Games app, but it does in The Athletic’s own app. Or you can play it for free online.

Read more: NYT Connections: Sports Edition Puzzle Comes Out of Beta

Hints for today’s Connections: Sports Edition groups

Here are four hints for the groupings in today’s Connections: Sports Edition puzzle, ranked from the easiest yellow group to the tough (and sometimes bizarre) purple group.

Yellow group hint: City of Brotherly Love.

Green group hint: NBA star.

Blue group hint: Grr! Meow! Roar!

Purple group hint: Think alphabet.

Answers for today’s Connections: Sports Edition groups

Yellow group: Philadelphia teams.

Green group: Associated with Larry Bird.

Blue group: Sports figures with animal names.

Purple group: Sports figures whose first names sound like two letters.

Read more: Wordle Cheat Sheet: Here Are the Most Popular Letters Used in English Words

What are today’s Connections: Sports Edition answers?

The yellow words in today’s Connections

The theme is Philadelphia teams. The four answers are 76ers, Flyers, Penn and Temple.

The green words in today’s Connections

The theme is associated with Larry Bird. The four answers are Celtics, French Lick, Pacers and Sycamores.

The blue words in today’s Connections

The theme is sports figures with animal names. The four answers are Bear Bryant, Cat Osterman, Catfish Hunter and Tiger Woods.

The purple words in today’s Connections

The theme is sports figures whose first names sound like two letters. The four answers are Casey Stengel (KC), CeeDee Lamb (CD), Katie Ledecky (KT) and Vijay Singh (VJ).

Technologies

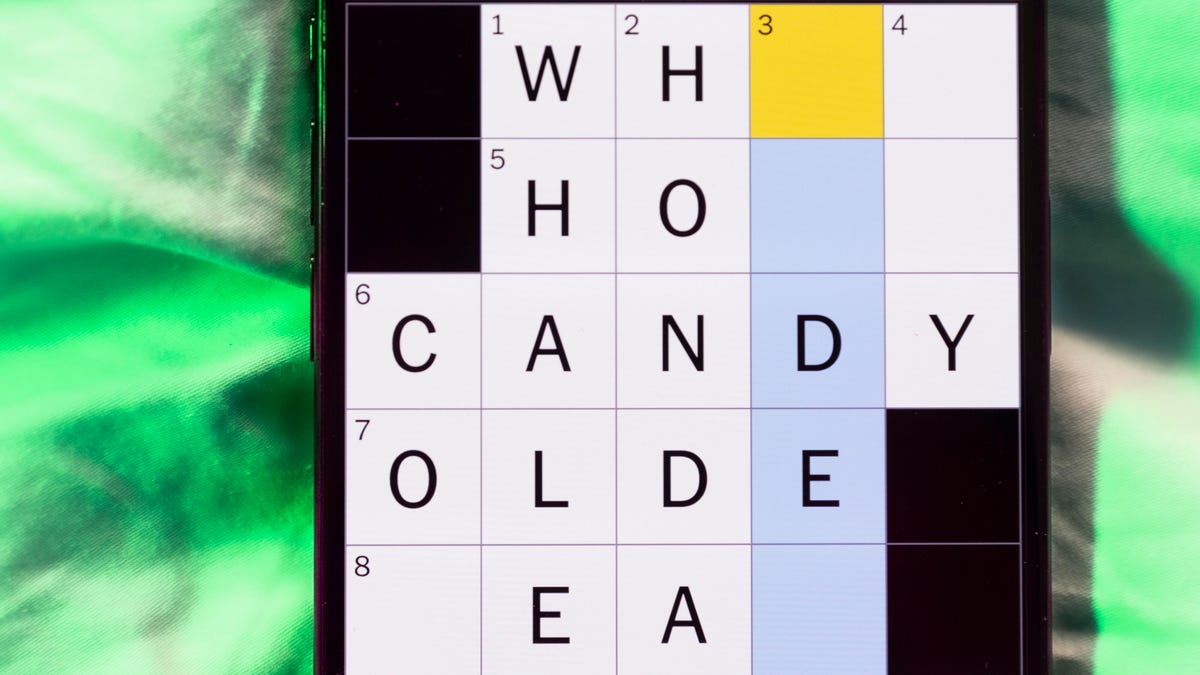

Today’s NYT Mini Crossword Answers for Thursday, March 12

Here are the answers for The New York Times Mini Crossword for March 12.

Looking for the most recent Mini Crossword answer? Click here for today’s Mini Crossword hints, as well as our daily answers and hints for The New York Times Wordle, Strands, Connections and Connections: Sports Edition puzzles.

Need some help with today’s Mini Crossword? I found 7-Across tricky. Read on for all the answers. And if you could use some hints and guidance for daily solving, check out our Mini Crossword tips.

If you’re looking for today’s Wordle, Connections, Connections: Sports Edition and Strands answers, you can visit CNET’s NYT puzzle hints page.

Read more: Tips and Tricks for Solving The New York Times Mini Crossword

Let’s get to those Mini Crossword clues and answers.

Mini across clues and answers

1A clue: Like jerk chicken and chicken vindaloo

Answer: SPICY

6A clue: Capital of Vietnam

Answer: HANOI

7A clue: «Well, would ya look at that!»

Answer: ILLBE

8A clue: Gem in an oyster

Answer: PEARL

9A clue: Thick roll of cash

Answer: WAD

Mini down clues and answers

1D clue: Part of a naval fleet

Answer: SHIP

2D clue: The «P» in I.P.A.

Answer: PALE

3D clue: Relative by marriage

Answer: INLAW

4D clue: King ___ (venomous snake)

Answer: COBRA

5D clue: Sign obeyed by merging traffic

Answer: YIELD

-

Technologies3 года ago

Technologies3 года agoTech Companies Need to Be Held Accountable for Security, Experts Say

-

Technologies3 года ago

Technologies3 года agoBest Handheld Game Console in 2023

-

Technologies3 года ago

Technologies3 года agoTighten Up Your VR Game With the Best Head Straps for Quest 2

-

Technologies4 года ago

Technologies4 года agoBlack Friday 2021: The best deals on TVs, headphones, kitchenware, and more

-

Technologies5 лет ago

Technologies5 лет agoGoogle to require vaccinations as Silicon Valley rethinks return-to-office policies

-

Technologies5 лет ago

Technologies5 лет agoVerum, Wickr and Threema: next generation secured messengers

-

Technologies4 года ago

Technologies4 года agoOlivia Harlan Dekker for Verum Messenger

-

Technologies4 года ago

Technologies4 года agoiPhone 13 event: How to watch Apple’s big announcement tomorrow