Technologies

Enhance Your Apple Watch Experience With These 8 Expert-Approved Tips

From taking control of Smart Stack to pausing your exercise rings, these tips will let you get the most out of your Apple Watch.

Apple’s smartwatch lineup continues to improve. With an updated design, an OS that continues to evolve and features that aim to make users more productive, there is plenty here to love. With the new Apple Watch series 11, Apple Watch SE 3 and the Apple Watch Ultra 3, you have multiple models to choose from, and all of them feature the new features in WatchOS 26.

With a variety of features that aim to make you more productive and stay active, it can be tricky to know which features are worth checking out. These are the eight features that I recommend to everyone.

Don’t miss any of our unbiased tech content and lab-based reviews. Add CNET as a preferred Google source.

Swipe between watch faces (again)

Until WatchOS 10.0, you could swipe from the left or right edge of the screen to switch active watch faces, a great way to quickly go from an elegant workday face to an exercise-focused one, for example. Apple removed that feature, likely because people were accidentally switching faces by brushing the edges of the screen.

However, the regular method involves more steps (touch and hold the face, swipe to change, tap to confirm), and people realized that the occasional surprise watch face change wasn’t really so bad. Therefore, as of version 10.2, including the current WatchOS 26, you can turn the feature on by toggling a setting: Go to Settings > Clock and turn on Swipe to Switch Watch Face.

Stay on top of your heart health with Vitals

Wearing your Apple Watch while sleeping offers a trove of information — and not just about how you slept last night. If you don the timepiece overnight, it tracks a number of health metrics. The Vitals app gathers that data and reports on the previous night’s heart rate, respiration, body temperature (on supported models) and sleep duration. The Vitals app can also show data collected during the previous seven days — tap the small calendar icon in the top-left corner.

If you own a watch model sold before Jan. 29, 2024, you’ll also see a blood oxygen reading. On newer watches in the US, that feature works differently because of an intellectual property fight: The watch’s sensors take a reading, and then send the data to the Health app on your iPhone. You can check it there, but it doesn’t show up in the Vitals app.

How is this helpful? The software builds a baseline of what’s normal for you. When the values stray outside normal ranges, such as irregular heart or respiratory rates, the Vitals app reports them as atypical to alert you. It’s not a medical diagnosis, but it can prompt you to get checked out and catch any troubles early.

Make the Wrist Flick gesture second nature

WatchOS 26 adds a new gesture that has quickly become a favorite. On the Apple Watch Series 9 and later, and the Apple Watch Ultra 2 and Ultra 3, Wrist Flick is a quick motion to dismiss incoming calls, notifications or really anything that pops up on the screen. Wrist Flick joins Double Tap as a way to interact with a watch even if you’re not in a position to tap the screen.

But what I like most about the gesture is that it’s also a shortcut for jumping back to the watch face. For example, when a Live Activity is automatically showing up in the Smart Stack, a quick flick of the wrist hides the stack. Or let’s say you’re configuring a feature in the Settings app that’s buried a few levels deep. You don’t need to repeatedly tap the back (<) button — just flick your wrist.

Make the Smart Stack work for you

The Smart Stack is a place to access quick information that might not fit into what Apple calls a «complication» (the things on the watch face other than the time itself, such as your Activity rings or the current outside temperature). When viewing the clock face, turn the digital crown clockwise or swipe from the bottom of the screen to view a series of tiles that show information such as the weather or suggested photo memories. This turns out to be a great spot for accessing features when you’re using a minimal watch face that has no complications.

Choose which Live Activities appear automatically

The Smart Stack is also where Live Activities appear: If you order a food delivery, for example, the status of the order appears as a tile in the Smart Stack (and on the iPhone lock screen). And because it’s a timely activity, the Smart Stack becomes the main view instead of the watch face.

Some people find that too intrusive. To disable it, on your watch open the Settings app, go to Smart Stack > Live Activities and turn off the Auto-Launch Live Activities option. You can also turn off Allow Live Activities in the same screen if you don’t want them disrupting your watch experience.

Apple’s apps that use Live Activities are listed there if you want to configure the setting per app, such as making active timers appear but not media apps such as Music. For third-party apps, open the Watch app on your iPhone, tap Smart Stack and find the settings there.

Add and pin favorite widgets in the Smart Stack

When the Smart Stack first appeared, its usefulness seemed hit or miss. Since then, Apple seems to have improved the algorithms that determine which widgets appear — instead of it being an annoyance, I find it does a good job of showing me information in context. But you can also pin widgets that will show up every time you open the stack.

For example, I use 10-minute timers for a range of things. Instead of opening the Timers app (via the App list or a complication), I added a single 10-minute timer to the Smart Stack. Here’s how:

- View the Smart Stack by turning the Digital Crown or swiping from the bottom of the screen.

- Tap the Edit button at the bottom of the stack. (In WatchOS 11, touch and hold the screen to enter the edit mode.)

- Tap the + button and scroll to the app you want to include (Timers, in this example).

- Tap a tile to add it to the stack; for Timers, there’s a Set Timer 10 minutes option.

- If you want it to appear higher or lower in the stack order, drag it up or down.

- Tap the checkmark button to accept the change.

The widget appears in the stack but it may get pushed down in favor of other widgets the watch thinks should have priority. In that case, you can pin it to the top of the list: While editing, tap the yellow Pin button. That moves it up but Live Activities can still take precedence.

Use the watch as a flashlight

You’ve probably used the flashlight feature of your phone dozens of times but did you know the Apple Watch can also be a flashlight? Instead of a dedicated LED (which phones also use as a camera flash), the watch’s full screen becomes the light emitter. It’s not as bright as the iPhone’s, nor can you adjust the beam width, but it’s perfectly adequate for moving around in the dark when you don’t want to disturb someone sleeping.

To activate the flashlight, press the side button to view Control Center and then tap the Flashlight button. That makes the entire screen white — turn the Digital Crown to adjust the brightness. It even starts dimmed for a couple of seconds to give you a chance to direct the light away so it doesn’t fry your eyes.

The flashlight also has two other modes: Swipe left to make the white screen flash on a regular cadence or swipe again to make the screen bright red. The flashing version can be especially helpful when you’re walking or running at night to make yourself more visible to vehicles.

Press the Digital Crown to turn off the Flashlight and return to the clock face.

Pause your Exercise rings if you’re traveling or ill

Closing your exercise, movement and standing rings can be great motivation for being more active. Sometimes, though, your body has other plans. Until WatchOS 11, if you became ill or needed to be on a long-haul trip, any streak of closing those rings that you built up would be dashed.

Now, the watch is more forgiving (and practical), letting you pause your rings without disrupting the streak. Open the Activity app and tap the Weekly Summary button in the top-left corner. Scroll all the way to the bottom (take a moment to admire your progress) and tap the Pause Rings button. Or, if you don’t need that extra validation, tap the middle of the rings and then tap Pause Rings. You can choose to pause them for today, until next week or month, or set a custom number of days.

When you’re ready to get back into your activities, go to the same location and tap Resume Rings.

Bypass the countdown to start a workout

Many workouts start with a three-second countdown to prep you to be ready to go. That’s fine and all, but usually when I’m doing an Outdoor Walk workout, for example, my feet are already on the move.

Instead of losing those steps, tap the countdown once to bypass it and get right to the calorie burn.

How to force-quit an app (and why you’d want to)

Don’t forget, the Apple Watch is a small computer on your wrist and every computer will have glitches. Every once in a while, for instance, an app may freeze or behave erratically.

On a Mac or iPhone, it’s easy to force a recalcitrant app to quit and restart, but it’s not as apparent on the Apple Watch. Here’s how:

- Double-press the Digital Crown to bring up the list of recent apps.

- Scroll to the one you want to quit by turning the crown or dragging with your finger.

- Swipe left on the app until you see a large red X button.

- Tap the X button to force-quit the app.

Keep in mind this is only for times when an app has actually crashed — as on the iPhone, there’s no benefit to manually quitting apps.

These are some of my favorite Apple Watch tips, but there’s a lot more to the popular smartwatch. Be sure to also check out why the Apple Watch SE 3 could be the sleeper hit of this year’s lineup and Vanessa Hand Orellana’s visit to the labs where Apple tests how the watches communicate.

Technologies

AI Slop Is Destroying the Internet. These Are the People Fighting to Save It

Technologies

The Sun’s Temper Tantrums: What You Should Know About Solar Storms

Solar storms are associated with the lovely aurora borealis, but they can have negative impacts, too.

Last month, Earth was treated to a massive aurora borealis that reached as far south as Texas. The event was attributed to a solar storm that lasted nearly a full day and will likely contend for the strongest of 2026. Such solar storms are usually fun for people on Earth, as we are protected from solar radiation by our planet’s atmosphere, so we can just enjoy the gorgeous greens and pretty purples in the night sky.

But solar storms are a lot more than just the aurora borealis we see, and sometimes they can cause real damage. There are several examples of this in recorded history, with the earliest being the Carrington Event, a solar storm that took place on Sept. 1, 1859. It remains the strongest solar storm ever recorded, where the world’s telegraph machines became overloaded with energy from it, causing them to shock their operators, send ghost messages and even catch on fire.

Things have changed a lot since the mid-1800s, and while today’s technology is a lot more resistant to solar radiation than it once was, a solar storm of that magnitude could still cause a lot of damage.

What is a solar storm?

A solar storm is a catchall term that describes any disturbance in the sun that involves the violent ejection of solar material into space. This can come in the form of coronal mass ejections, where clouds of plasma are ejected from the sun, or solar flares, which are concentrated bursts of electromagnetic radiation (aka light).

A sizable percentage of solar storms don’t hit Earth, and the sun is always belching material into space, so minor solar storms are quite common. The only ones humans tend to talk about are the bigger ones that do hit the Earth. When this happens, it causes geomagnetic storms, where solar material interacts with the Earth’s magnetic fields, and the excitations can cause issues in everything from the power grid to satellite functionality. It’s not unusual to hear «solar storm» and «geomagnetic storm» used interchangeably, since solar storms cause geomagnetic storms.

Solar storms ebb and flow on an 11-year cycle known as the solar cycle. NASA scientists announced that the sun was at the peak of its most recent 11-year cycle in 2024, and, as such, solar storms have been more frequent. The sun will metaphorically chill out over time, and fewer solar storms will happen until the cycle repeats.

This cycle has been stable for hundreds of millions of years and was first observed in the 18th century by astronomer Christian Horrebow.

How strong can a solar storm get?

The Carrington Event is a standout example of just how strong a solar storm can be, and such events are exceedingly rare. A rating system didn’t exist back then, but it would have certainly maxed out on every chart that science has today.

We currently gauge solar storm strength on four different scales.

The first rating that a solar storm gets is for the material belched out of the sun. Solar flares are graded using the Solar Flare Classification System, a logarithmic intensity scale that starts with B-class at the lowest end, and then increases to C, M and finally X-class at the strongest. According to NASA, the scale goes up indefinitely and tends to get finicky at higher levels. The strongest solar flare measured was in 2003, and it overloaded the sensors at X17 and was eventually estimated to be an X45-class flare.

CMEs don’t have a named measuring system, but are monitored by satellites and measured based on the impact they have on the Earth’s geomagnetic field.

Once the material hits Earth, NOAA uses three other scales to determine how strong the storm was and which systems it may impact. They include:

- Geomagnetic storm (G1-G5): This scale measures how much of an impact the solar material is having on Earth’s geomagnetic field. Stronger storms can impact the power grid, electronics and voltage systems.

- Solar radiation storm (S1-S5): This measures the amount of solar radiation present, with stronger storms increasing exposure to astronauts in space and to people in high-flying aircraft. It also describes the storm’s impact on satellite functionality and radio communications.

- Radio blackouts (R1-R5): Less commonly used but still very important. A higher R-rating means a greater impact on GPS satellites and high-frequency radios, with the worst case being communication and navigation blackouts.

Solar storms also cause auroras by exciting the molecules in Earth’s atmosphere, which then light up as they «calm down,» per NASA. The strength and reach of the aurora generally correlate with the strength of the storm. G1 storms rarely cause an aurora to reach further south than Canada, while a G5 storm may be visible as far south as Texas and Florida. The next time you see a forecast calling for a big aurora, you can assume a big solar storm is on the way.

How dangerous is a solar storm?

The overwhelming majority of solar storms are harmless. Science has protections against the effects of solar storms that it did not have back when telegraphs were catching on fire, and most solar storms are small and don’t pose any threat to people on the surface since the Earth’s magnetic field protects us from the worst of it.

That isn’t to say that they pose no threats. Humans may be exposed to ionizing radiation (the bad kind of radiation) if flying at high altitudes, which includes astronauts in space. NOAA says that this can happen with an S2 or higher storm, although location is really important here. Flights that go over the polar caps during solar storms are far more susceptible than your standard trip from Chicago to Houston, and airliners have a whole host of rules to monitor space weather, reroute flights and monitor long-term radiation exposure for flight crews to minimize potential cancer risks.

Larger solar storms can knock quite a few systems out of whack. NASA says that powerful storms can impact satellites, cause radio blackouts, shut down communications, disrupt GPS and cause damaging power fluctuations in the power grid. That means everything from high-frequency radio to cellphone reception could be affected, depending on the severity.

A good example of this is the Halloween solar storms of 2003. A series of powerful solar flares hit Earth on Oct. 28-31, causing a solar storm so massive that loads of things went wrong. Most notably, airplane pilots had to change course and lower their altitudes due to the radiation wreaking havoc on their instruments, and roughly half of the world’s satellites were entirely lost for a few days.

A paper titled Flying Through Uncertainty was published about the Halloween storms and the troubles they caused. Researchers note that 59% of all satellites orbiting Earth at the time suffered some sort of malfunction, like random thrusters going offline and some shutting down entirely. Over half of the Earth’s satellites were lost for days, requiring around-the-clock work from NASA and other space agencies to get everything back online and located.

Earth hasn’t experienced a solar storm on the level of the Carrington Event since it occurred in 1859, so the maximum damage it could cause in modern times is unknown. The European Space Agency has run simulations, and spoiler alert, the results weren’t promising. A solar storm of that caliber has a high chance of causing damage to almost every satellite in orbit, which would cause a lot of problems here on Earth as well. There were also significant risks of electrical blackouts and damage. It would make one heck of an aurora, but you might have to wait to post it on social media until things came back online.

Do we have anything to worry about?

We’ve mentioned two massive solar storms with the Halloween storms and the Carrington Event. Such large storms tend to occur very infrequently. In fact, those two storms took place nearly 150 years apart. Those aren’t the strongest storms yet, though. The very worst that Earth has ever seen were what are known as Miyake events.

Miyake events are times throughout history when massive solar storms were thought to have occurred. These are measured by massive spikes in carbon-14 that were preserved in tree rings. Miyake events are few and far between, but science believes at least 15 such events have occurred over the past 15,000 years. That includes one in 12350 BCE, which may have been twice as large as any other known Miyake event.

They currently hold the title of the largest solar storms that we know of, and are thought to be caused by superflares and extreme solar events. If one of these happened today, especially one as large as the one in 12350 BCE, it would likely cause widespread, catastrophic damage and potentially threaten human life.

Those only appear to happen about once every several hundred to a couple thousand years, so it’s exceedingly unlikely that one is coming anytime soon. But solar storms on the level of the Halloween storms and the Carrington Event have happened in modern history, and humans have managed to survive them, so for the time being, there isn’t too much to worry about.

Technologies

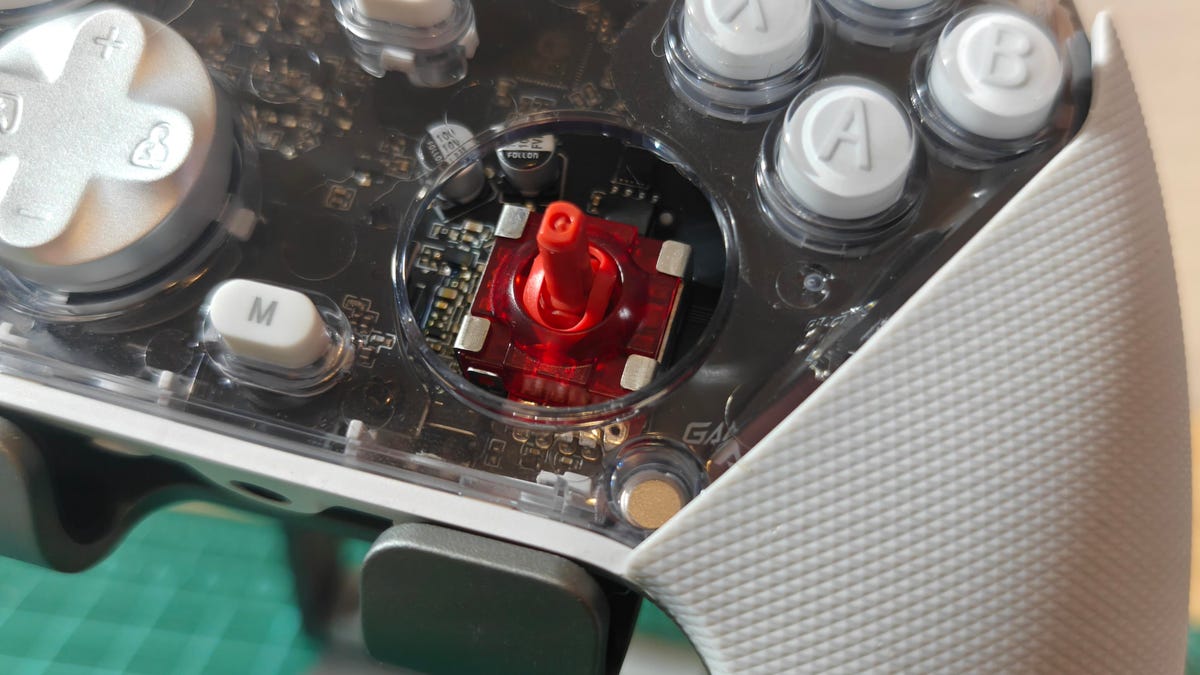

TMR vs. Hall Effect Controllers: Battle of the Magnetic Sensing Tech

The magic of magnets tucked into your joysticks can put an end to drift. But which technology is superior?

Competitive gamers look for every advantage they can get, and that drive has spawned some of the zaniest gaming peripherals under the sun. There are plenty of hardware components that actually offer meaningful edges when implemented properly. Hall effect and TMR (tunnel magnetoresistance or tunneling magnetoresistance) sensors are two such technologies. Hall effect sensors have found their way into a wide variety of devices, including keyboards and gaming controllers, including some of our favorites like the GameSir Super Nova.

More recently, TMR sensors have started to appear in these devices as well. Is it a better technology for gaming? With multiple options vying for your lunch money, it’s worth understanding the differences to decide which is more worthy of living inside your next game controller or keyboard.

How Hall effect joysticks work

We’ve previously broken down the difference between Hall effect tech and traditional potentiometers in controller joysticks, but here’s a quick rundown on how Hall effect sensors work. A Hall effect joystick moves a magnet over a sensor circuit, and the magnetic field affects the circuit’s voltage. The sensor in the circuit measures these voltage shifts and maps them to controller inputs. Element14 has a lovely visual explanation of this effect here.

The advantage this tech has over potentiometer-based joysticks used in controllers for decades is that the magnet and sensor don’t need to make physical contact. There’s no rubbing action to slowly wear away and degrade the sensor. So, in theory, Hall effect joysticks should remain accurate for the long haul.

How TMR joysticks work

While TMR works differently, it’s a similar concept to Hall effect devices. When you move a TMR joystick, it moves a magnet in the vicinity of the sensor. So far, it’s the same, right? Except with TMR, this shifting magnetic field changes the resistance in the sensor instead of the voltage.

There’s a useful demonstration of a sensor in action here. Just like Hall effect joysticks, TMR joysticks don’t rely on physical contact to register inputs and therefore won’t suffer the wear and drift that affects potentiometer-based joysticks.

Which is better, Hall effect or TMR?

There’s no hard and fast answer to which technology is better. After all, the actual implementation of the technology and the hardware it’s built into can be just as important, if not more so. Both technologies can provide accurate sensing, and neither requires physical contact with the sensing chip, so both can be used for precise controls that won’t encounter stick drift. That said, there are some potential advantages to TMR.

According to Coto Technology, who, in fairness, make TMR sensors, they can be more sensitive, allowing for either greater precision or the use of smaller magnets. Since the Hall effect is subtler, it relies on amplification and ultimately requires extra power. While power requirements vary from sensor to sensor, GameSir claims its TMR joysticks use about one-tenth the power of mainstream Hall effect joysticks. Cherry is another brand highlighting the lower power consumption of TMR sensors, albeit in the brand’s keyboard switches.

The greater precision is an opportunity for TMR joysticks to come out ahead, but that will depend more on the controller itself than the technology. Strange response curves, a big dead zone (which shouldn’t be needed), or low polling rates could prevent a perfectly good TMR sensor from beating a comparable Hall effect sensor in a better optimized controller.

The power savings will likely be the advantage most of us really feel. While it won’t matter for wired controllers, power savings can go a long way for wireless ones. Take the Razer Wolverine V3 Pro, for instance, a Hall effect controller offering 20 hours of battery life from a 4.5-watt-hour battery with support for a 1,000Hz polling rate on a wireless connection. Razer also offers the Wolverine V3 Pro 8K PC, a near-identical controller with the same battery offering TMR sensors. They claim the TMR version can go for 36 hours on a charge, though that’s presumably before cranking it up to an 8,000Hz polling rate — something Razer possibly left off the Hall effect model because of power usage.

The disadvantage of the TMR sensor would be its cost, but it appears that it’s negligible when factored into the entire price of a controller. Both versions of the aforementioned Razer controller are $199. Both 8BitDo and GameSir have managed to stick them into reasonably priced controllers like the 8BitDo Ultimate 2, GameSir G7 Pro and GameSir Cyclone 2.

So which wins?

It seems TMR joysticks have all the advantages of Hall effect joysticks and then some, bringing better power efficiency that can help in wireless applications. The one big downside might be price, but from what we’ve seen right now, that doesn’t seem to be much of an issue. You can even find both technologies in controllers that cost less than some potentiometer models, like the Xbox Elite Series 2 controller.

Caveats to consider

For all the hype, neither Hall effect nor TMR joysticks are perfect. One of their key selling points is that they won’t experience stick drift, but there are still elements of the joystick that can wear down. The ring around the joystick can lose its smoothness. The stick material can wear down (ever tried to use a controller with the rubber worn off its joystick? It’s not pleasant). The linkages that hold the joystick upright and the springs that keep it stiff can loosen, degrade and fill with dust. All of these can impact the continued use of the joystick, even if the Hall effect or TMR sensor itself is in perfect operating order.

So you might not get stick drift from a bad sensor, but you could get stick drift from a stick that simply doesn’t return to its original resting position. That’s when having a controller that’s serviceable or has swappable parts, like the PDP Victrix Pro BFG, could matter just as much as having one with Hall effect or TMR joysticks.

-

Technologies3 года ago

Technologies3 года agoTech Companies Need to Be Held Accountable for Security, Experts Say

-

Technologies3 года ago

Technologies3 года agoBest Handheld Game Console in 2023

-

Technologies3 года ago

Technologies3 года agoTighten Up Your VR Game With the Best Head Straps for Quest 2

-

Technologies4 года ago

Technologies4 года agoBlack Friday 2021: The best deals on TVs, headphones, kitchenware, and more

-

Technologies5 лет ago

Technologies5 лет agoGoogle to require vaccinations as Silicon Valley rethinks return-to-office policies

-

Technologies5 лет ago

Technologies5 лет agoVerum, Wickr and Threema: next generation secured messengers

-

Technologies4 года ago

Technologies4 года agoOlivia Harlan Dekker for Verum Messenger

-

Technologies4 года ago

Technologies4 года agoiPhone 13 event: How to watch Apple’s big announcement tomorrow