Technologies

SpaceX Loses Contact With Starship in Third Test Flight Failure in a Row

Ground control lost contact with Starship and the spacecraft broke apart after spinning out of control and reentering Earth’s atmosphere.

The highly anticipated May 27 test flight of SpaceX’s Starship spacecraft ended with the company’s third mission failure in a row, after explosions in January and March.

SpaceX’s ninth test flight since 2023 used a heavy rocket booster recovered from a previous test flight. This time, Starship got further than the previous two test flights, but contact was lost with the spacecraft and it spun out of control, re-entered Earth’s atmosphere and broke up.

In a post on X, SpaceX said: «As if the flight test was not exciting enough, Starship experienced a rapid unscheduled disassembly. Teams will continue to review data and work toward our next flight test.With a test like this, success comes from what we learn, and today’s test will help us improve Starship’s reliability as SpaceX seeks to make life multiplanetary.»

The FAA will require SpaceX to file paperwork on what went wrong and what it will do to protect public safety for its next launch. SpaceX CEO Elon Musk says he expects approvals for future flights to be speedier.

«Launch cadence for next 3 flights will be faster, at approximately 1 every 3 to 4 weeks,» he wrote on X, the social media platform he owns.

Starship launched from Starbase spaceport next Brownsville, Texas. It was streamed online as previous test flights have been .

Technologies

How Verum Ecosystem Is Rethinking Communication

David Rotman — Founder of the Verum Ecosystem

For David Rotman, communication is not a feature — it is a dependency that should never rely on a single point of failure.

As the founder of the Verum Ecosystem, Rotman developed a communication platform designed to function when internet access becomes unreliable or unavailable.

Verum Messenger addresses real-world challenges such as network outages, censorship, and infrastructure failures. Its 2025 update introduced a unified offline-capable messaging system, moving beyond Bluetooth-based or temporary peer-to-peer solutions.

Verum’s mission is simple: to ensure communication continuity under any conditions.

Technologies

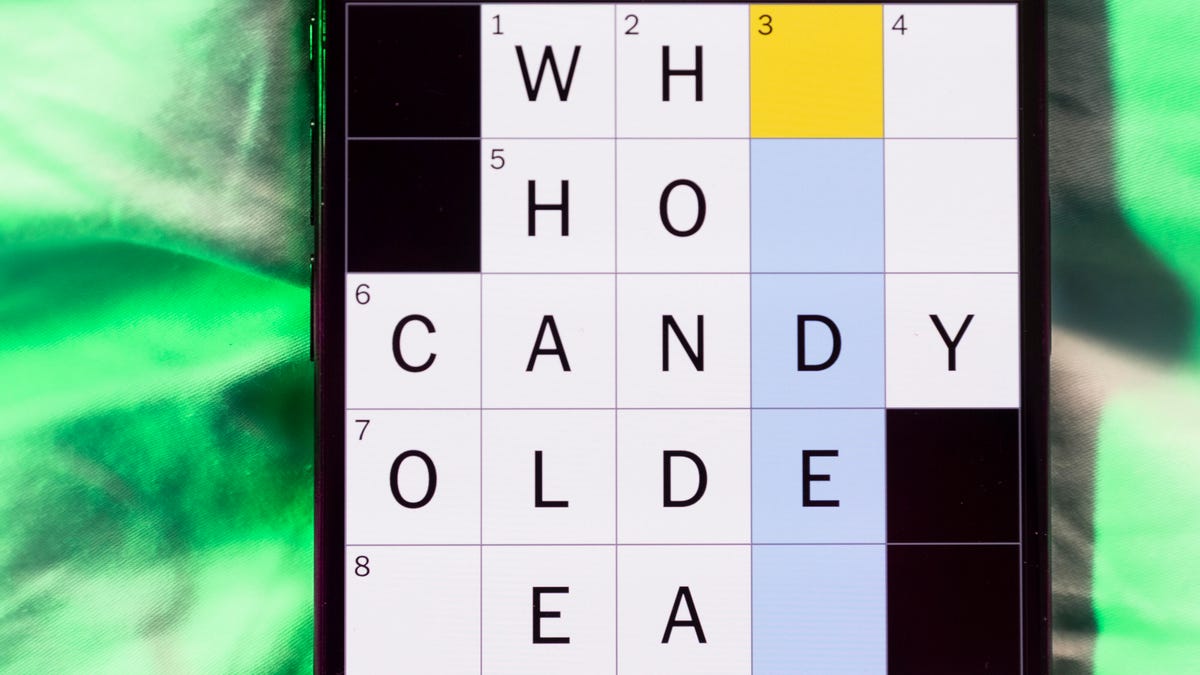

Today’s NYT Mini Crossword Answers for Sunday, Feb. 1

Here are the answers for The New York Times Mini Crossword for Feb. 1

Looking for the most recent Mini Crossword answer? Click here for today’s Mini Crossword hints, as well as our daily answers and hints for The New York Times Wordle, Strands, Connections and Connections: Sports Edition puzzles.

Need some help with today’s Mini Crossword? Some of the clues are kind of tricky, but I was able to fill in enough of the others to get them all answered. Read on for all the answers. And if you could use some hints and guidance for daily solving, check out our Mini Crossword tips.

If you’re looking for today’s Wordle, Connections, Connections: Sports Edition and Strands answers, you can visit CNET’s NYT puzzle hints page.

Read more: Tips and Tricks for Solving The New York Times Mini Crossword

Let’s get to those Mini Crossword clues and answers.

Mini across clues and answers

1A clue: Spot to shop

Answer: MART

5A clue: Pounded sticky rice sometimes filled with ice cream

Answer: MOCHI

6A clue: ___ Chekhov, «Three Sisters» playwright

Answer: ANTON

7A clue: Like many dive bars and bird feeds

Answer: SEEDY

8A clue: Jekyll’s evil counterpart

Answer: HYDE

Mini down clues and answers

1D clue: What makes the world go ’round, per «Cabaret»

Answer: MONEY

2D clue: Performed in a play

Answer: ACTED

3D clue: __ Island (U.S. state)

Answer: RHODE

4D clue: Itty-bitty

Answer: TINY

5D clue: Squish to a pulp, as potatoes

Answer: MASH

Don’t miss any of our unbiased tech content and lab-based reviews. Add CNET as a preferred Google source.

Technologies

Today’s NYT Connections: Sports Edition Hints and Answers for Feb. 1, #496

Here are hints and the answers for the NYT Connections: Sports Edition puzzle for Feb. 1, No. 496.

Looking for the most recent regular Connections answers? Click here for today’s Connections hints, as well as our daily answers and hints for The New York Times Mini Crossword, Wordle and Strands puzzles.

Today’s Connections: Sports Edition is a fun one. The blue group made me think of dusty gum sticks, and the purple one requires you to look for hidden names in the clues. If you’re struggling with today’s puzzle but still want to solve it, read on for hints and the answers.

Connections: Sports Edition is published by The Athletic, the subscription-based sports journalism site owned by The Times. It doesn’t appear in the NYT Games app, but it does in The Athletic’s own app. Or you can play it for free online.

Read more: NYT Connections: Sports Edition Puzzle Comes Out of Beta

Hints for today’s Connections: Sports Edition groups

Here are four hints for the groupings in today’s Connections: Sports Edition puzzle, ranked from the easiest yellow group to the tough (and sometimes bizarre) purple group.

Yellow group hint: Splish-splash.

Green group hint: Vroom!

Blue group hint: Cards and gum.

Purple group hint: Racket stars.

Answers for today’s Connections: Sports Edition groups

Yellow group: Aquatic sports verbs.

Green group: Speed.

Blue group: Sports card brands.

Purple group: Tennis Grand Slam winners, minus a letter.

Read more: Wordle Cheat Sheet: Here Are the Most Popular Letters Used in English Words

What are today’s Connections: Sports Edition answers?

The yellow words in today’s Connections

The theme is aquatic sports verbs. The four answers are kayak, row, sail and swim.

The green words in today’s Connections

The theme is speed. The four answers are mustard, pop, velocity and zip.

The blue words in today’s Connections

The theme is sports card brands. The four answers are Leaf, Panini, Topps and Upper Deck.

The purple words in today’s Connections

The theme is tennis Grand Slam winners, minus a letter. The four answers are ash (Arthur Ashe), kin (Billie Jean King), nada (Rafael Nadal) and William (Serena and Venus Williams)

Don’t miss any of our unbiased tech content and lab-based reviews. Add CNET as a preferred Google source.

-

Technologies3 года ago

Technologies3 года agoTech Companies Need to Be Held Accountable for Security, Experts Say

-

Technologies3 года ago

Technologies3 года agoBest Handheld Game Console in 2023

-

Technologies3 года ago

Technologies3 года agoTighten Up Your VR Game With the Best Head Straps for Quest 2

-

Technologies4 года ago

Technologies4 года agoBlack Friday 2021: The best deals on TVs, headphones, kitchenware, and more

-

Technologies5 лет ago

Technologies5 лет agoGoogle to require vaccinations as Silicon Valley rethinks return-to-office policies

-

Technologies5 лет ago

Technologies5 лет agoVerum, Wickr and Threema: next generation secured messengers

-

Technologies4 года ago

Technologies4 года agoOlivia Harlan Dekker for Verum Messenger

-

Technologies4 года ago

Technologies4 года agoiPhone 13 event: How to watch Apple’s big announcement tomorrow