Technologies

VPN trackers: Everything you need to know

Not all VPNs actually care about your privacy. Choose one that doesn’t track you.

Public concern over web tracking is higher than ever. That concern has been mounting for well over a decade, but we’re no better off now than we were then — pervasive tracking and unbridled data collection is still the lay of the land all these years later. Websites and apps deploy trackers that follow us all over the web and share the information they collect with third parties. Our ISPs collect hordes of data every time we go online, then sell it off to the highest bidder.

As a result, consumers are increasingly turning to virtual private networks to help them evade these tracking practices. But what can you do when it’s the VPNs themselves that are doing the tracking? As with any app or online service, it’s important to do your research and make sure you choose a provider that actually takes your privacy seriously. Just because a VPN company boldly states that it cares about your privacy doesn’t mean it’s true.

VPNs are supposed to protect your privacy online and help you fight back against the machine hell-bent on exploiting your data for its own gain. And gaining privacy from tracking is one of the main reasons you should seek the help of a VPN. But it can be difficult to sort through the various ways VPNs might track you. Here’s what to know about the different trackers VPNs use, and how they separate the best VPNs from the ones you should avoid.

First-party trackers vs. third-party trackers

Not all trackers are the same. For example, there’s a crucial difference between first-party and third-party trackers. There’s a similarly vital distinction between trackers used on a VPN’s website versus the ones inside a VPN’s app. In both cases, the second option will have much greater implications on your privacy than the former.

First-party trackers, also known as cookies, are used and stored by the websites you visit. They’re used for things like remembering your preferences, geographic region, language settings and what you put in your shopping cart. They’re also used by website administrators to collect data as you visit their sites, helping them better understand your behavior and figure out what will keep you on their site longer and buying more of their products and services.

Basically, first-party trackers are there to provide you with a smoother experience as you visit the websites you frequent. It would be annoying to have to set all your preferences each and every time you visit a site and to have to re-add each individual item to your shopping cart every time you click away from your cart.

A VPN company may use first-party trackers on its website to save your settings, display account-specific information after you log in and see what marketing channel brought you to its site.

Third-party trackers are different in that they are created by entities other than the site you’re visiting. After a site puts these trackers on your computer via your browser, they follow you across the websites you visit. They are injected into a website using a tag or a script and are accessible on any site that loads the third-party’s tracking code. But the big difference is that they’re used to track your online behavior and make money from you, rather than improve your online experience.

In simpler terms, third-party trackers exist to help companies bombard you with targeted advertisements based on your online browsing activity. Targeted advertising is big business, and there are mountains of cash to be made at the expense of your digital privacy.

That said, Apple and Google have begun shifting their policies regarding the use of third-party trackers in their respective mobile app marketplaces and have provided users more transparency and a much greater element of control when it comes to restricting how apps are able to track them. Google even proposed a solution to eliminating the use of third-party trackers altogether. That proposal, however, turned out to be a failure after people began pointing out the ways in which Google’s proposed alternative would make it even easier for the company to track and identify you for targeted advertising. Google was forced back to the drawing board and ended up shelving the idea for at least two years. Still, the industry is slowly showing signs of progress.

If a VPN company is using third-party trackers on its website for marketing purposes or to enhance your experience on the site itself, the tracking is easy to block in most cases. But when a VPN tracks you on its app, the alarm bells should start going off. In-app trackers should make you seriously concerned about what that VPN is really up to (Spoiler: It’s to make money from sharing your data) and should ultimately steer you away from that VPN altogether.

Why would VPN companies need to track you through their apps?

Simple answer: They don’t. Their apps would function just as well for you whether they tracked you or not.

But many VPN companies will employ trackers in their apps regardless of how much they say they care about your privacy. Those VPNs put users’ privacy at risk so they can make as much money as possible. And what some of these VPN apps track and share with third parties is actually quite alarming. This is the biggest reason we advise you to avoid using free VPNs.

What data is being collected by these trackers and who is it shared with?

The scope of data collection will vary greatly from one VPN to another, and will differ in terms of whether the trackers are being deployed on the VPN’s website or within the app itself. But let’s focus on trackers embedded within VPN apps themselves.

There are VPN apps out there that will track and share things like your user ID, device or advertising ID, usage data and even your location. They track this information just to sell it on to third parties for targeted advertising purposes, making money at the expense of your digital privacy. Any VPN engaging in such activity should be avoided at all costs.

When we say your data is being shared with third-party entities, we mean entities like data brokers and advertisers that put profits ahead of ethics. That information is also being shared with sites like Google and Facebook, meaning that even if you don’t have a Facebook account and you’re doing your best to stay away from big tech data hogs, your data is still being shared with them.

Unfortunately, far too many VPN apps will track and share your data with all kinds of third parties. That’s why it’s crucial to scrutinize the data sharing practices of any VPN you’re considering. (We do this as part of our review process and thoroughly vet a VPN’s data policies before we recommend it to anyone.)

The concern is real

VPNs are often quick to claim that the data they’re tracking and sharing with third parties is anonymized and not identifiable or tied to your personal information. That sounds great, but something like a device ID can still be used to identify you personally when other data points tied to your online behavior and interactions with the app are matched to that ID. It doesn’t actually take that much to connect the dots and identify you online.

Researchers have shown that 99.98% of users could be re-identified in any anonymized dataset using only 15 data points. The more data points an app is collecting about you, the easier it is for others to identify you online, even if the data being collected isn’t necessarily personally identifiable information.

Find out what data they’re collecting and tracking

Luckily, it’s becoming easier and easier to see what VPN companies are collecting and tracking when you use their apps. For one, reputable VPNs are getting increasingly transparent about what data they collect and what kinds of trackers they may or may not be implementing on their sites and apps. VPNs know that their reputations rely on actually walking the walk when it comes to protecting user privacy. So transparency is key.

On top of that, since Apple introduced its App Tracking Transparency functionality in its App Store, you now have a much clearer picture of any application’s tracking practices. You can now see if any app you’re looking to download wants to track you and share your data with third parties and you can easily deny those permissions. Google introduced similar functionality with its recent Android 12 release.

In addition to scrutinizing a VPN app’s tracking practices, you’ll want to scour its privacy policy to see what kinds of trackers it uses, what data it collects and who it shares that data with. If you notice that a provider you’re looking at is sharing user data with an abundance of third parties, or if the provider isn’t up front or totally transparent about its practices, then it’s best to move along and find something else.

When you do your research, you’ll see that the best VPNs don’t resort to such unscrupulous tracking practices. Part of our review process includes vetting the data collection practices of each provider. Though the VPNs we recommend, like Surfshark, NordVPN and ExpressVPN, may collect certain types of connection data when you use their apps, they don’t deploy in-app trackers.

While these VPNs may deploy cookies on their websites, they’re transparent about exactly what those cookies are there for and how they help improve website functionality and aid in advertising their services across the web. Their third-party trackers can also be blocked via your browser settings.

Always check a VPN’s privacy policies, and their apps in the App Store and the Play Store to learn more about the trackers they deploy on their websites and apps. The important thing to keep in mind here is that the apps of our recommended VPNs will not track you like the apps of some other less-than-trustworthy VPNs.

How to fight back against tracking

If you don’t want your VPN app to track you, you’ll want to take a few precautions.

With Apple’s App Tracking Transparency in place, iOS apps have to get your explicit permission before they are able to track you. If you deny that permission, the app developer won’t have access to your device’s advertising ID and won’t be able to track you or share that ID with third parties.

You can even deny any and all apps on your iOS device from even asking you if they can track you in the first place. All you’d need to do is head over to your settings menu and disable tracking. Similarly, if you’re an Android user, you can manage your app permissions to limit tracking on an app-by-app basis by navigating to your Privacy Dashboard.

Keep in mind that even if you deny an app access to your advertising ID, that doesn’t necessarily prevent it from sharing other data with third parties. A new bit of investigative research from Top10VPN showed that 85% of the top free VPNs in Apple’s US App Store will still share your data with third-party advertisers even after you’ve explicitly denied their requests to track you. Even if they don’t have access to your advertising ID — according to Top10VPN’s research — these free VPN apps still track and share information like your IP address, device name, language, device model and iOS version with advertisers without your consent. This is all information that can be used to identify you, and the research is a pointed reminder of why we recommend staying away from free VPNs.

If you’re concerned about VPN companies using trackers on their websites and sharing data with third parties, then you can use a privacy-focused browser like Brave or Firefox, or use a tool like the Duck Duck Go’s browser extension to your current browser. Options like these will help you to easily prevent websites from tracking you as you browse the web. If you’re not willing to part ways with your existing browser or install an extension, there are various settings you should change to protect your privacy and limit tracking.

Next steps

Websites and apps will routinely do whatever they can to track your activity across the internet to churn as much money out of the targeted ad machine as possible. But the tide is finally turning as people have begun to realize exactly how invasive the practice is and how detrimental it can be to our digital privacy.

More and more options are available to defend against tracking practices, and VPN companies are becoming increasingly transparent with consumers with regards to how they approach the subject and many are ditching tracking altogether. Unfortunately, many VPN companies still continue the practice and are sharing all kinds of tracking data with third parties. If you’re an iOS user, just take a look through the VPNs available in the App Store and take a peek at their «nutrition label» and you’ll see what we mean.

If you already have a VPN app installed on your device, check to see if it’s tracking you and sharing your data with third parties. If it is, it’s time to wipe it from your device for good and never look back, because it’s compromising your privacy rather than protecting it — which is the opposite of what a VPN should be doing.

Technologies

The Witcher 3, Kingdom Come Deliverance 2 Bring the Heat to Xbox Game Pass

Two amazing games will be available soon for Xbox Game Pass subscribers.

The second half of February and early March could be considered one of the best stretches in recent memory for Xbox Game Pass subscribers. The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt, widely regarded as one of the best games of the past decade, and Kingdom Come: Deliverance 2 headline a lineup that leans heavily into sprawling, choice-driven adventures but does throw in some football to mix things up a bit.

Xbox Game Pass offers hundreds of games you can play on your Xbox Series X, Xbox Series S, Xbox One, Amazon Fire TV, smart TV, PC or mobile device, with prices starting at $10 a month. While all Game Pass tiers offer you a library of games, Game Pass Ultimate ($30 a month) gives you access to the most games, as well as Day 1 games, meaning they hit Game Pass the day they go on sale.

Here are all the latest games subscribers can play on Game Pass. You can also check out other games the company added to the service in early February, including Madden NFL 26.

The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt – Complete Edition

Available on Feb. 19 for Game Pass Ultimate and Premium Game Pass subscribers.

The Witcher 3 came out 10 years ago, and it’s still being praised as one of the best games ever made. To celebrate, developer CD Projekt Red is bringing over The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt Complete Edition to Xbox Game Pass. Subscribers will be able to play The Witcher 3 and its expansions, Hearts of Stone and Blood and Wine. Players once more take on the role of monster-slayer Geralt, who goes on an epic search for his daughter, Ciri. As he pieces together what happened to her, he comes across vicious monsters, devious spirits, and the most evil of humans who seek to end his quest.

Death Howl

Available on Feb. 19 for Game Pass Ultimate, Game Pass Premium and PC Game Pass subscribers.

Death Howl is a dark fantasy tactical roguelike that blends turn-based grid combat with deck-building mechanics. Players move across compact battlefield maps, weighing positioning and card synergies to survive increasingly difficult encounters. Progression comes through incremental upgrades that reshape each run. Battles reward careful planning, as overextending or mismanaging your hand can quickly end a run.

EA Sports College Football 26

Available on Feb. 19 for Game Pass Ultimate subscribers.

EA Sports College Football 26 delivers a new take on college football gameplay with enhanced offensive and defensive mechanics, smarter AI and dynamic play-calling that reflects real strategic football systems. Featuring over 2,800 plays and more than 300 real-world coaches with distinct schemes, it offers expanded Dynasty and Road to Glory modes where team building and personnel decisions matter. On the field, dynamic substitutions, improved blocking and coverage logic make matches feel more fluid and tactical.

Dice A Million

Available on Feb. 25 for Game Pass Ultimate and PC Game Pass subscribers.

Dice A Million centers on rolling and managing dice to build toward increasingly higher scores. Each round asks players to weigh risk against reward, deciding when to bank points and when to push for bigger combinations. Progression introduces modifiers and new rules that subtly shift probabilities, making runs feel distinct while keeping the core loop focused on calculated gambling.

Towerborne

Available on Feb. 26 for Game Pass Ultimate, PC, and Premium Game Pass subscribers.

After months in preview, Towerborne will get its full release on Xbox Game Pass. The fast-paced action game blends procedural dungeons and light RPG progression, with players fighting through waves of enemies. You’ll unlock permanent upgrades between runs and equip weapons, spells and talents that change how combat feels each time. The core loop pushes risk versus reward as you dive deeper into tougher floors, adapting builds on the fly, and mastering movement and timing to survive increasingly chaotic battles.

Final Fantasy 3

Available on March 3 for Game Pass Ultimate, Premium and PC Game Pass subscribers.

Another Final Fantasy game is coming to Xbox Game Pass. This time, it’s Final Fantasy 3, originally released on the Famicom (the Japanese version of the NES) back in 1990. Since then, Final Fantasy 3 has been ported to a slew of devices and operating systems, including the Nintendo Wii, iOS and Android. Now, you’ll be able to play on your Xbox or PC with a Game Pass subscription. A new group of heroes is once again tasked with saving the world before it’s covered in darkness. Four orphans from the village of Ur find a Crystal of Light in a secret cave, which tasks them as the new Warriors of Light. They’ll have to stop Xande, an evil wizard looking to use the power of darkness to become immortal.

Kingdom Come: Deliverance 2

Available on March 3 for Game Pass Ultimate, Premium and PC Game Pass subscribers.

Last year was stacked with amazing games, and Kingdom Come: Deliverance 2 was one of the best. Developer Warhorse Studios’ RPG series takes place in the real medieval kingdom of Bohemia, which is now the Czech Republic, and tasks players with a somewhat realistic gaming experience where you have to use the weapons, armor and items from those times. The sequel picks up right after the first game (also on Xbox Game Pass) as Henry of Skalitz is attacked by bandits, which starts a series of events that disrupts the entire country.

Games leaving Game Pass in February

For February, Microsoft is removing four games. If you’re still playing them, now’s a good time to finish up what you can before they’re gone for good on Feb. 28.

For more on Xbox, discover other games available on Game Pass now, and check out our hands-on review of the gaming service. You can also learn about recent changes to Game Pass.

Technologies

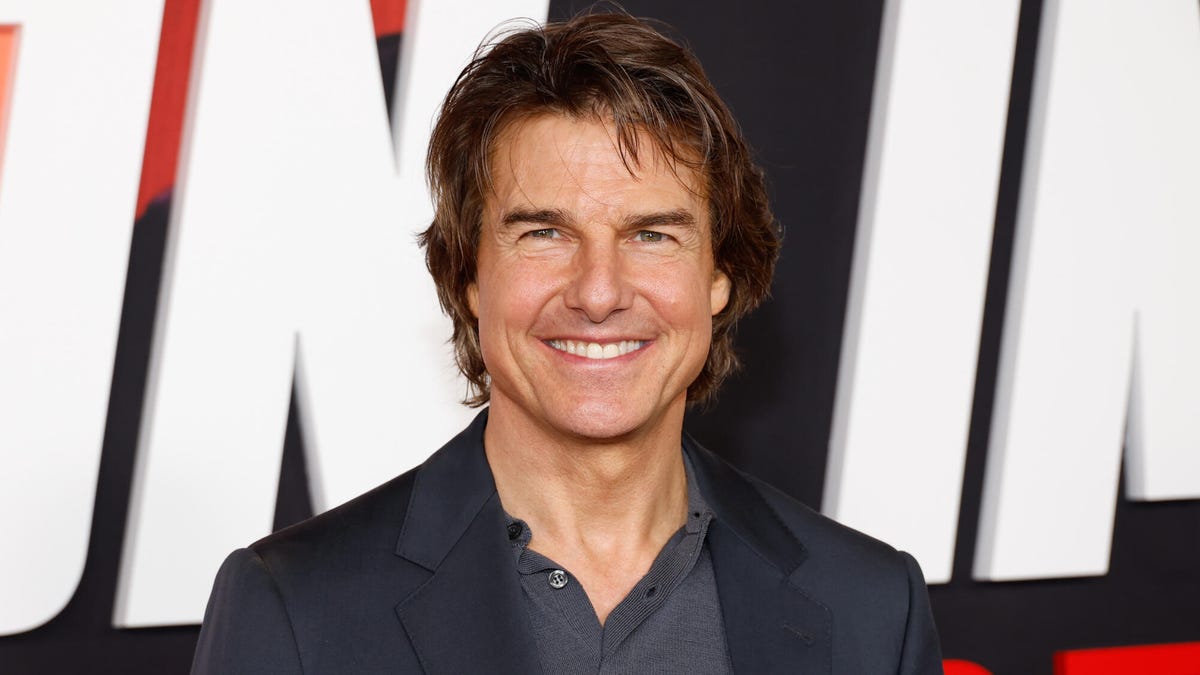

Tom Cruise and Brad Pitt Trade Blows in Latest AI Slop Video, and Hollywood Won’t Stand for It

While some Hollywood icons are feeling doom and gloom over the AI-generated clip, labor unions are fighting back with legal threats.

Brad Pitt and Tom Cruise are trading blows in a viral AI-generated clip on social media, sparking backlash from the film industry. Chinese company ByteDance’s new video generation model, Seedance 2.0, allowed people to create fictional videos of real likenesses with short prompts. Irish filmmaker Ruairi Robinson used two lines to generate the clip of Pitt and Cruise fighting.

If ByteDance sounds familiar to you, it’s because the company also owns TikTok internationally, though it recently sold its US ownership of the social media and video-sharing platform to US companies. Oracle, MGX and Silver Lake each hold a 15% stake.

The actors in this latest viral AI slop video still don’t look like perfect re-creations — close-up shots of the fake Brad Pitt’s face, especially, have an «uncanny valley,» dreamlike AI look where the cuts blend into his flesh a little too smoothly. However, a CNET survey from earlier Tuesday showed that while 94% of US adults believe they encounter AI slop on social media, just 44% say they’re confident they can tell real videos from AI-generated ones.

One of the most inflammatory parts of the Pitt-Cruise video is the dialogue, as the computerized facsimiles of the actors fight over a supposed assassination plot regarding Jeffrey Epstein, the convicted sex offender who maintained ties to rich and powerful people worldwide. The two actors’ likenesses became a vehicle to push conspiracy theories that have been picking up steam as the millions of pages of redacted emails, receipts and other documents that make up the Epstein files continue to trickle out of the US Department of Justice.

Hollywood is fighting back as AI-generated content consumes and spits out actor likenesses and copyrighted content alike. Major studios and their labor forces alike have united to push back against the precedent set by the viral AI video.

According to The Hollywood Reporter, the Motion Picture Association demanded that ByteDance «immediately cease its infringing activity» through Seedance. SAG-AFTRA, the labor union that represents Hollywood performers, released a statement on Friday saying it «stands with the studios» in condemning the Seedance video generation model.

The Screen Actors Guild specifically pointed to Seedance’s unauthorized use of members’ faces, likenesses and voices as a threat that could put actors out of work.

«Seedance 2.0 disregards law, ethics, industry standards and basic principles of consent,» the actors’ guild said in its statement.

Representatives for the MPA and SAG-AFTRA didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.

Similar videos generated by Seedance have depicted Star Wars characters dueling with lightsabers as well as Marvel superheroes Spider-Man and Captain America brawling. Disney issued a cease-and-desist order to ByteDance on Friday in response to these videos, which it alleges constitute copyright infringement, according to the BBC.

A representative for ByteDance didn’t immediately respond to CNET’s request for comment, but issued a statement to the BBC saying it is «taking steps to strengthen current safeguards as we work to prevent the unauthorized use of intellectual property and likeness by users.»

Following the viral incident, ByteDance updated its tool to prevent people from uploading images of real people for AI-generated content, but it remains to be seen how effective that policy will be. Certainly, it won’t curb the output of videos depicting fictional masked or anthropomorphic characters like Spider-Man or Mickey Mouse.

As AI models continue to create mediocre copies of cultural icons, this won’t be the first — or last — legal battleground for AI video generation.

Technologies

Today’s NYT Connections Hints, Answers and Help for Feb. 18, #983

Here are some hints and the answers for the NYT Connections puzzle for Feb. 18 #983.

Looking for the most recent Connections answers? Click here for today’s Connections hints, as well as our daily answers and hints for The New York Times Mini Crossword, Wordle, Connections: Sports Edition and Strands puzzles.

Today’s NYT Connections puzzle was great fun for me, as I’m the co-author of two pop-culture encyclopedias, one about the 1970s, and 1980s and the other about the 1990s. Two of the categories are retro-themed! Read on for clues and today’s Connections answers.

The Times has a Connections Bot, like the one for Wordle. Go there after you play to receive a numeric score and to have the program analyze your answers. Players who are registered with the Times Games section can now nerd out by following their progress, including the number of puzzles completed, win rate, number of times they nabbed a perfect score and their win streak.

Read more: Hints, Tips and Strategies to Help You Win at NYT Connections Every Time

Hints for today’s Connections groups

Here are four hints for the groupings in today’s Connections puzzle, ranked from the easiest yellow group to the tough (and sometimes bizarre) purple group.

Yellow group hint: Farrah hair.

Green group hint: Totally tubular!

Blue group hint: Bock-bock!

Purple group hint: Can refer to a dairy product or a cosmetic.

Answers for today’s Connections groups

Yellow group: Retro hair directives.

Green group: Retro slang for cool.

Blue group: Chicken descriptors.

Purple group: ____ cream.

Read more: Wordle Cheat Sheet: Here Are the Most Popular Letters Used in English Words

What are today’s Connections answers?

The yellow words in today’s Connections

The theme is retro hair directives. The four answers are crimp, curl, feather and tease.

The green words in today’s Connections

The theme is retro slang for cool. The four answers are bad, fly, rad and wicked.

The blue words in today’s Connections

The theme is chicken descriptors. The four answers are bantam, crested, free-range and leghorn.

The purple words in today’s Connections

The theme is ____ cream. The four answers are heavy, shaving, sour and topical.

-

Technologies3 года ago

Technologies3 года agoTech Companies Need to Be Held Accountable for Security, Experts Say

-

Technologies3 года ago

Technologies3 года agoBest Handheld Game Console in 2023

-

Technologies3 года ago

Technologies3 года agoTighten Up Your VR Game With the Best Head Straps for Quest 2

-

Technologies4 года ago

Technologies4 года agoBlack Friday 2021: The best deals on TVs, headphones, kitchenware, and more

-

Technologies5 лет ago

Technologies5 лет agoGoogle to require vaccinations as Silicon Valley rethinks return-to-office policies

-

Technologies5 лет ago

Technologies5 лет agoVerum, Wickr and Threema: next generation secured messengers

-

Technologies4 года ago

Technologies4 года agoOlivia Harlan Dekker for Verum Messenger

-

Technologies4 года ago

Technologies4 года agoiPhone 13 event: How to watch Apple’s big announcement tomorrow