Technologies

‘Weather Whiplash’ Could Be a Disturbing New Normal in a Weird, Warming World

After praying for rain for weeks, the US state that saw some of the year’s biggest wildfires in 2022 found itself soon suffering a deadly deluge.

This story is part of CNET Zero, a series that chronicles the impact of climate change and explores what’s being done about the problem.

I’ve lived in the high desert of the southwestern US most of my life, primarily in New Mexico and Colorado. In those four decades, I’ve never seen it as dry here as in 2022. In all that time, I’ve also never seen it as wet as this year.

In northern New Mexico, the year began with months of unseasonal heat, dryness and extreme wind that fueled the largest wildfire of the year in the lower 48 states. It burned through 340,000 acres of the Sangre de Cristo mountains and destroyed or damaged over a thousand homes and other structures.

Then, in the middle of June, the annual monsoon rains thankfully arrived to douse the fires. But they stayed a couple months longer and dumped nearly twice as much moisture as the previous year (or the year before that). In fact, we were still seeing some monsoon pattern precipitation several weeks later than normal.

There’s a term for this remarkably rapid turnaround in weather patterns that an increasing number of scientists have begun to use, both in the mainstream media and academic publications: weather whiplash.

«The huge shift in weather you experienced in New Mexico this summer is a perfect example,» Jennifer Francis, acting deputy director at the Woodwell Climate Research Center in Massachusetts tells me.

Francis is lead author on a paper published in September in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres on measuring weather whiplash events, which can be loosely defined as abrupt swings in weather conditions from one extreme to another.

At my home in the high desert this year, those swings translated into a Spring filled with smoke, heat, wind and the first emergency alert system notice I’d ever received warning me to get off the road immediately due to an approaching dust storm. By July the scene changed to one filled with rain, mud and more alerts, this time warning of flash flooding.

«Weather patterns are getting «stuck» in place more often, causing persistent heatwaves, drought, stormy periods, and even cold spells to happen more often,» Francis explained via email.

Her work shows all this stalled weather is connected to the rapid warming of the Arctic, which impacts the jet stream and in turn affects weather further south.

«These stuck weather patterns sometimes come to an abrupt end by changing abruptly to a very different pattern. This is weather whiplash.»

The phrase has been increasingly used in climate science circles for the past several years, but Francis points to a number of other instances of the phenomenon on full, sobering display in 2022 alone.

A July heatwave immediately followed exceptionally wet, cool weather in the Pacific Northwest and Northern Rockies in June. This turnaround was most dramatic in the Yellowstone region, where historic flooding in the first month of summer took many by surprise and claimed hundreds of homes but, somewhat miraculously, no lives. Shortly afterwards, temperatures soared several degrees above average and the region dried out.

Earlier in the year the inverse played out in Texas, where a spell of 67 consecutive dry, hot winter days in Dallas were followed by the city’s heaviest rains in 100 years, leading to flash flooding and a declaration of disaster by the state’s Governor.

Seasonal See-Saw

From late March until early June, much of northern New Mexico saw no measurable precipitation for a stretch of more than 70 days. Even for the current era, which many scientists suspect is the beginning of a megadrought in the southwestern US, that’s unusually dry.

This dryness, along with unseasonable heat and often extreme winds whipped up the embers of two controlled burns in the Santa Fe National Forest that had been secretly smoldering for months. Two wildfires sprang to life, eventually combining to form the 340,000-acre Calf Canyon-Hermit’s Peak fire complex.

The inferno burned homes, ranches, businesses and livestock, but didn’t claim any human lives – at least, not directly. Tens of thousands were evacuated from nearby cities and villages for weeks as fire devoured some of the state’s most rugged and beautiful terrain over the course of more than two months.

I visited some of the impacted communities to witness the total disruption and devastation while waiting to see if the flames would continue to push closer to my own community near Taos, less than 20 miles from the northwest edge of the fire.

For weeks it looked as though a nuclear bomb had been detonated just over the ridge of mountains near my home. A pyrocumulus mushroom cloud of smoke from the fire reached up into the atmosphere, a constant reminder of impending doom one valley over.

Sometimes the wind would shift and blow all that smoke our direction. It was possible to see this coming almost an hour in advance as a brown stream of smog would suddenly obscure the mountains. As it finally reached us, our eyes would water, our lungs would begin to burn and everything we wore or carried would take on the aroma of a barbecue. Minutes later, the sun would be blotted out on an otherwise sunny day. They were all sunny days back then.

My family would retreat inside every time the smoke came, of course. Then, in early June, another fire ignited on the opposite side of our community from where the megablaze was burning. We found ourselves surrounded. No matter which way the wind blew, there was a good chance it would blow smoke in our faces.

At this point our daughter was quarantined at home with COVID. We faced the very apocalyptic choice of keeping the windows open for better anti-viral ventilation or closing them to keep the smoke out. It wasn’t a particularly hard choice. We closed the windows. Inhaling smoke certainly isn’t great for getting over COVID, after all.

Then, in mid-June, both the weather and its impact took dramatic turns. The annual monsoon rains arrived right on time, and with an unusual intensity. Ironically, this is how New Mexico’s largest ever wildfire ended up claiming human lives after the flames had stopped spreading.

The burn scars left by wildfires absorb less moisture than healthy landscapes with plenty of vegetation, and that led to flash flooding. June and July in northern New Mexico saw repeated cycles of heavy rains, including a particularly heavy storm on July 21 that deluged the Calf Canyon-Hermit’s Peak burn scar. A flash flood tore through the Tecolote Canyon subdivision outside the city of Las Vegas, New Mexico, sweeping tons of mud, rocks, burned trees and even vehicles down the creek drainage. Tragically, three people were caught in the flood and died.

In the span of weeks, citizens in New Mexico went from fleeing fires to fleeing floods. Whiplash might describe the disjointed nature of this past summer, but it doesn’t begin to capture the anxiety brought on by this new realization that life in the 21st century might be about being ready for absolutely anything.

In June I was hauling water to my off-grid home in the back of a truck, 200 gallons at a time, and praying for the monsoon to arrive. The following month I was digging trenches to divert as much water as possible out of my driveway to lessen the persistent rain’s irritating habit of turning it into a muddy quagmire. This is to say nothing of the background anxiety created by nearby fires, floods and at least one epic wind event that took the roof off a neighbor’s house.

The Climate Connection

At least one group of researchers predicted this before it happened. Well, sort of.

On April 1, just five days before that massive fire in New Mexico sprang to life, a paper was published in the journal Science Advances titled «Climate change increases risk of extreme rainfall following wildfire in the western United States.»

The paper describes how scientists used climate models to predict that if global warming continues unabated, the western US will begin to see many more instances of extreme wildfires followed by extreme rainfall. They didn’t wait decades to see their predictions come true. It happened just weeks later.

«I would qualify what happened in New Mexico as extreme precipitation following extreme wildfires,» UCLA and National Center for Atmospheric Research climate scientist Daniel Swain, one of the authors of the study, told me. «Some of those fires were literally still burning pretty vigorously when the rain started. You really can’t get any whiplashier than that.»

Swain is one of a number of climate scientists digging into the data to determine what is creating this new, very 21st century sort of see-saw. One of the main factors, he says, is that the warming of the planet is accelerating the water, or hydrologic, cycle that moves moisture from surface water to the atmosphere and back again via precipitation.

«You actually get an exponential increase in the water-vapor-holding capacity of the atmosphere,» he explains.

Basically, for every degree centigrade of warming, the atmosphere can hold 7% more moisture. These increases compound over time, sort of like interest in a bank account, which provides the exponential acceleration of extreme rainfall events that are more frequent and more intense.

Swain describes our atmosphere as a sponge that grows ever larger as it warms, periodically soaking up potentially larger amounts of moisture and then dumping it all at once on some unfortunate locale. But this expanding sponge is also exacerbating dryness in places where it extracts an increasing amount of water out of the landscape.

This means drier dry periods and wetter precipitation events, sometimes back-to-back. Whiplash.

Swain cautions that it’s too soon to know how much of the weather whiplash experienced in northern New Mexico this year can truly be blamed on climate change versus just basic bad luck and the natural variation and randomness that we’d see in our weather patterns even without global warming.

Climate scientists have developed so-called «weather attribution» models that quantify the effects of climate change directly on specific weather events like what was experienced this year in New Mexico, but the process can take several months or longer.

Weirder than Warming

When I first started covering climate two decades ago, a climatologist told me the phrase «global warming» wouldn’t fully describe what was going to happen to our environment and that it would be more like «global weirding.»

That phrase never caught on, but I’m starting to think weather whiplash might be its appropriate successor.

For decades now, talk about the warming climate has focused on increasing temperatures, but usually these are increasing average temperatures. However, we don’t experience climate in the aggregate. We live it day-to-day as weather that is increasingly extreme.

«If you get 20 inches of rainfall distributed as half an inch a day for 40 days it’s a very different picture than getting 20 inches of rainfall because it rains 10 inches one day and 10 inches the next,» Swain suggests. «The average might be the same, but you’re living in a completely different world.»

In other words, our experience of climate change can’t be fully captured by talking about how much temperatures or sea levels or rainfall are rising. It’s the extremes and the weirdness and the chaotic swings from one state to another that tell the real story and inflict the most trauma.

At the point this summer when wildfires were burning on both sides of our community I had a weird flashback to my childhood. One of my favorite things to read as a kid in the previous century was Choose Your Own Adventure books. They had this intoxicating ability to provide both an escape and agency at the same time.

It feels like we could use a little more of both things right now. Life today has the feel of all the potential adventures in those books happening back-to-back and often simultaneously. The only choice is to be ready for anything.

Technologies

MWC Barcelona 2026: All the New Tech, Phones, Wearables and AI We Expect to See

This year’s Mobile World Congress starts Monday and will be packed with reveals from Xiaomi, Honor, Nvidia and more.

Every year, the moment we witness the very earliest signs of spring, CNET takes its cue to decamp to Barcelona for Mobile World Congress.

This is the world’s most important mobile show, and one of the most exciting events in the tech calendar. This year, we’re sending a bigger team to bring you all the news from the show as it happens.

It’s set to be a bonanza of new phones and wearables, with the odd robot thrown in for good measure. Sure, some of the fun tech we see at MWC never makes it out into the wider world, but we’ve also seen some of our most beloved tech debut at the show over the years — so expect a little of both.

Big themes are set to include AI and 6G, and with keynotes from SpaceX and Qualcomm, we’ll no doubt get a solid glimpse of the future of mobile. With Gemini in everything and satellite dominance on the horizon, it’s an exciting time for the industry.

Here’s more of what we expect to see.

What are the key dates for MWC?

MWC 2026 is set to run from March 2 to 5, although we’ll be in town a couple of days beforehand to report on some of the big launch events scheduled for this weekend. Don’t miss Xiaomi’s launch event on Feb. 28 and Honor’s event on March 1.

How to watch along

No matter how far away you live from Spain, there’s no need to feel like you’re missing out. The best place for all the latest MWC news is on our CNET live blog.

We’ve been attending this show for decades (this is MWC’s 20th year in Barcelona, by the way), and we have a team of experienced reporters and reviewers on the ground.

We’ll show you everything we deem interesting and important, and we’re not just admiring new products from afar. We’re touching, tinkering with and trying not to drop them, so be sure to follow us across Bluesky, Instagram, TikTok, X and YouTube, too.

What phones to expect at MWC 2026

For the past few years, Chinese phone-makers have dominated MWC, and 2026 looks to be no different.

The first big phone launch event is scheduled for 6 a.m. PT Saturday, Feb. 28, when we expect Xiaomi to unveil its latest camera-focused flagship. We loved the Xiaomi 15 Ultra, and the 14 Ultra before it, so we’re excited to see what the company has in store for us. A teaser image hints at its partnership with premium camera brand Leica and promises a «new wave of imagery.»

Next up, we have Honor on Sunday, March 1, when the company has said it will unveil its Magic V6 phone, alongside the MagicPad 4 and MagicBook Pro 14. Perhaps more exciting still, Honor has said it will give us a first glimpse of a working version of its Robot Phone, and will also unveil a humanoid robot at its event.

For other phone-makers, MWC is likely to serve as more of a victory lap for its existing devices — particularly Samsung, which held its own event in San Francisco this week to unveil the flagship S26 series. Motorola will be in town, likely showing off its Razr, which just like the Samsung Galaxy TriFold, has yet to be seen much in Europe.

On the whole, MWC 2026 is likely to be a big show for foldable phones, which, according to Ben Wood, CMO and chief analyst at CCS Insight, «is now becoming quite a mature category.»

Another major trend in the phone space is likely to be a focus on batteries, particularly silicon carbon-based tech, Wood said in an MWC preview session. «We’re expecting to see phones with some of the biggest batteries we’ve seen for a long time, [with] fast charging — perhaps 300-watt charging — being introduced,» he added.

What other tech to expect at MWC 2026

After the early flops that were the Humane AI Pin and the Rabbit R1, we’re seeing more companies moving to jump on the wearable AI bandwagon. We expect to see a number of devices and demos pop up at MWC — perhaps trying to beat OpenAI and Jony Ive to the punch.

This will include AI- and AR-based glasses, said CCS Insight analyst Ben Hatton during the firm’s briefing session. «We are expecting to see a huge number of glasses on show this year, not just from Meta, but also from the smaller players, [like] TCL and Oppo, looking to take a slice of the pie,» he said.

One of the key challenges for these companies will be differentiation, Hatton said. «Ultimately, there’s still a long way to go before these become generally mass market products,» he added, pointing out that at this stage, compelling use cases are still a bit thin on the ground.

It’s been two years since Samsung launched the Galaxy Ring at MWC, and smart rings have been fairly thin on the ground ever since — although Oura CEO Tom Hale is slated to speak at the show. We’re not necessarily expecting to see any new rings this year, but there’s always an outside chance.

Much more likely to show up are a slew of new laptops and tablets. They rarely get top billing at MWC, but we’ll keep an eye out for the most exciting launches. There’s also likely to be some intriguing concepts on show from the likes of Lenovo and Samsung Display, which is responsible for the tech behind the new Galaxy S26 Ultra’s scene-stealing Privacy Display.

The big themes: AI, 6G and beyond

No surprises here that AI will, of course, be a major theme at MWC. For the past few years, Google has dominated the AI conversation at the event by showcasing Gemini’s capabilities and its widespread integration. Will this year be any different? Probably not, but that doesn’t mean the AI conversation has stalled.

We expect to see more sophisticated AI agents that are more deeply integrated into wearables, offering live translation, more actionable health insights and more personalized experiences. Some of the biggest players in the AI game will be present, including Nvidia and Qualcomm, on the hardware side. They’ll likely have saved some juicy announcements for the show and, hopefully, have some exciting demos we can try out.

Wind the clock back a decade, and everyone was talking about 5G and what a dramatic difference it was going to make to our lives. Now that 5G is old news, we’re looking forward to 6G. Most discussions about 6G so far have focused on its impact on the industry, but that doesn’t mean there’s nothing to be excited about.

At the Web Summit in November, Qualcomm CEO Cristiano Amon told me that 6G will make our phones faster than ever and connect us to an «always-sensing network.» This could include wearables, smart devices, cars and even robots. No doubt, Amon will expound on this subject further during his MWC keynote, which is all about 6G and AI.

Another theme likely to be prevalent at the show is the role of satellites in enhancing network connectivity. SpaceX President Gwynne Shotwell will be on stage to talk about Starlink, and all the world’s biggest carriers will have their own booths where they’ll show us what they’re doing to tap into the latest network technologies.

Technologies

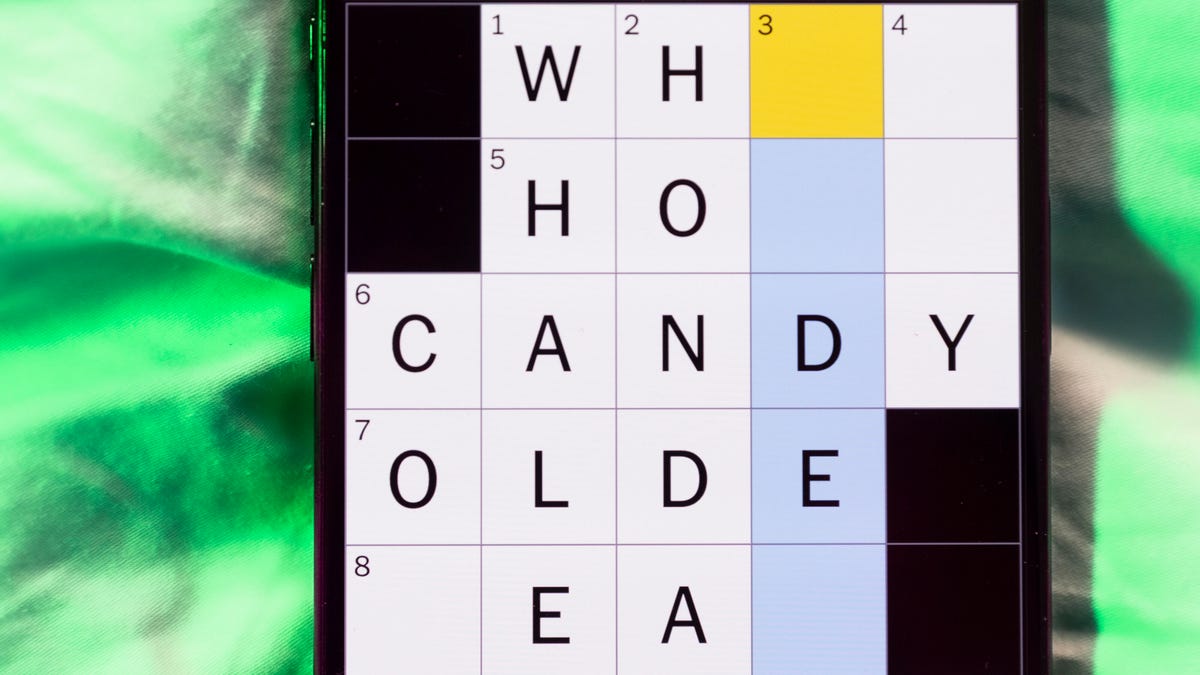

Today’s NYT Mini Crossword Answers for Saturday, Feb. 28

Here are the answers for The New York Times Mini Crossword for Feb. 28.

Looking for the most recent Mini Crossword answer? Click here for today’s Mini Crossword hints, as well as our daily answers and hints for The New York Times Wordle, Strands, Connections and Connections: Sports Edition puzzles.

Need some help with today’s Mini Crossword? As is usual for Saturday, it’s pretty long, and should take you longer than the normal Mini. A bunch of three-initial terms are used in this one. Read on for all the answers. And if you could use some hints and guidance for daily solving, check out our Mini Crossword tips.

If you’re looking for today’s Wordle, Connections, Connections: Sports Edition and Strands answers, you can visit CNET’s NYT puzzle hints page.

Read more: Tips and Tricks for Solving The New York Times Mini Crossword

Let’s get to those Mini Crossword clues and answers.

Mini across clues and answers

1A clue: Rock’s ___ Leppard

Answer: DEF

4A clue: Cry a river

Answer: SOB

7A clue: Clean Air Act org.

Answer: EPA

8A clue: Org. that pays the Bills?

Answer: NFL

9A clue: Nintendo console with motion sensors

Answer: WII

10A clue: ___-quoted (frequently said)

Answer: OFT

11A clue: With 13-Across, narrow gap between the underside of a house and the ground

Answer: CRAWL

13A clue: See 11-Across

Answer: SPACE

14A clue: Young lady

Answer: GAL

15A clue: Ooh and ___

Answer: AAH

17A clue: Sports org. for Scottie Scheffler

Answer: PGA

18A clue: «Hey, just an F.Y.I. …,» informally

Answer: PSA

19A clue: When doubled, nickname for singer Swift

Answer: TAY

20A clue: Socially timid

Answer: SHY

Mini down clues and answers

1D clue: Morning moisture

Answer: DEW

2D clue: «Game of Thrones» or Homer’s «Odyssey»

Answer: EPICSAGA

3D clue: Good sportsmanship

Answer: FAIRPLAY

4D clue: White mountain toppers

Answer: SNOWCAPS

5D clue: Unrestrained, as a dog at a park

Answer: OFFLEASH

6D clue: Sandwich that might be served «triple-decker»

Answer: BLT

12D clue: Common battery type

Answer: AA

14D clue: Chat___

Answer: GPT

16D clue: It’s for horses, in a classic joke punchline

Answer: HAY

Technologies

Ultrahuman Ring Pro Brings Better Battery Life, More Action and Analysis

The company’s new flagship smart ring stores more data, too. But that doesn’t really help Americans.

Sick of your smart ring’s battery not holding up? Ultrahuman’s new $479 Ring Pro smart ring, unveiled on Friday, offers up to 15 days of battery life on a single charge. The Ring Pro joins the company’s $349 Ring Air, which boosts health tracking, thanks to longer battery life, increased data storage, improved speed and accuracy and a new heart-rate sensing architecture. The ring works in conjunction with the latest Pro charging case.

Ultrahuman also launched its Jade AI, which can act as an agent based on analysis of current and historical health data. Jade can synthesize data from across the company’s products and is compatible with its Rings.

«With industry-leading hardware paired with Jade biointelligence AI, users can now take real-time actionable interventions towards their health than ever before,» said Mohit Kumar, CEO of Ultrahuman.

No US sales

That hardware isn’t available in the US, though, thanks to the ongoing ban on Ultrahuman’s Rings sales here, stemming from a patent dispute with its competitor, Oura Ring. It’s available for preorder now everywhere else and is slated to ship in March. Jade’s available globally.

Ultrahuman says the Ring Pro boosts battery life to about 15 days in Chill mode — up to 12 days in Turbo — compared to a maximum of six days for the Air. The Pro charger’s battery stores enough for another 45 days, which you top off with Qi-compatible wireless charging. In addition, the case incorporates locator technology via the app and a speaker, as well as usability features such as haptic notifications and a power LED.

The ring can also retain up to 250 days of data versus less than a week for the cheaper model. Ultrahuman redesigned the heart-rate sensor for better signal quality. An upgraded processor improves the accuracy of the local machine learning and overall speed.

It’s offered in gold, silver, black and titanium finishes, with available sizes ranging from 5 to 14.

Jade’s Deep Research Mode is the cross-ecosystem analysis feature, which aggregates data from Ring and Blood Vision and the company’s subscription services, Home and M1 CGM, to provide historical trends, offer current recommendations and flag potential issues, as well as trigger activities such as A-fib detection. Ultrahuman plans to expand its capabilities to include health-adjacent activities, such as ordering food.

Some new apps are also available for the company’s PowerPlug add-on platform, including capabilities such as tracking GLP-1 effects, snoring and respiratory analysis and migraine management tools.

-

Technologies3 года ago

Technologies3 года agoTech Companies Need to Be Held Accountable for Security, Experts Say

-

Technologies3 года ago

Technologies3 года agoBest Handheld Game Console in 2023

-

Technologies3 года ago

Technologies3 года agoTighten Up Your VR Game With the Best Head Straps for Quest 2

-

Technologies4 года ago

Technologies4 года agoBlack Friday 2021: The best deals on TVs, headphones, kitchenware, and more

-

Technologies5 лет ago

Technologies5 лет agoGoogle to require vaccinations as Silicon Valley rethinks return-to-office policies

-

Technologies5 лет ago

Technologies5 лет agoVerum, Wickr and Threema: next generation secured messengers

-

Technologies4 года ago

Technologies4 года agoOlivia Harlan Dekker for Verum Messenger

-

Technologies4 года ago

Technologies4 года agoiPhone 13 event: How to watch Apple’s big announcement tomorrow