Technologies

Major Energy Breakthrough: Milestone Achieved in US Fusion Experiment

For the first time, the National Ignition Facility officially achieved ignition in a fusion reactor.

It was touted as a «major scientific breakthrough» and, it seems, the rumors were true: On Tuesday, scientists at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory announced that they have, for the first time, achieved net energy gain in a controlled fusion experiment.

«We have taken the first tentative steps toward a clean energy source that could revolutionize the world,» Jill Hruby, administrator of the National Nuclear Security Administration, said in a press conference Tuesday.

The triumph comes courtesy of the National Ignition Facility at LLNL in San Francisco. This facility has long tried to master nuclear fusion — a process that powers the sun and other stars — in an effort to harness the massive amounts of energy released during the reaction because, as Hruby points out, all that energy is «clean» energy.

Despite decades of effort, however, there had been a major kink in these fusion experiments: the amount of energy used to achieve fusion has far outweighed the energy coming out. As part of the NIF mission, scientists had long hoped to achieve «ignition,» where the energy output is «greater than or equal to laser drive energy.»

Some experts have remained skeptical that such a feat was even possible with fusion reactors currently in operation. But slowly, NIF pushed forward. In August last year, LLNL revealed it had come close to this threshold by generating around 1.3 megajoules (a measure of energy) against a laser drive using 1.9 megajoules.

But on Dec. 5, LLNL’s scientists say, they managed to cross the threshold.

They achieved ignition.

All in all, this achievement is cause for celebration. It’s the culmination of decades of scientific research and incremental progress. It’s a critical, albeit small, step forward, to demonstrate that this type of reactor can, in fact, generate energy.

«Reaching ignition in a controlled fusion experiment is an achievement that has come after more than 60 years of global research, development, engineering and experimentation,» Hruby said.

«It’s a scientific milestone,» Arati Prabhakar, policy director for the White House Office of Science and Technology, said during the conference, «but it’s also an engineering marvel.»

Still, a fully operational platform, connected to the grid and used to power homes and businesses, likely remains a few decades away.

«This is one igniting capsule at one time,» Kim Budil, director of LLNL, said. «To realize commercial fusion energy you have to do many things. You have to be able to produce many, many fusion ignition events per minute, and you have to have a robust system of drivers to enable that.»

So how did we get here? And what does the future hold for fusion energy?

Simulating stars

The underlying physics of nuclear fusion has been well understood for almost a century.

Fusion is a reaction between the nuclei of atoms that occurs under extreme conditions, like those present in stars. The sun, for instance, is about 75% hydrogen and, because of the all-encompassing heat and pressure at its core, these hydrogen atoms are squeezed together, fusing to form helium atoms.

If atoms had feelings, it would be easy to say they don’t particularly like being squished together. It takes a lot of energy to do so. Stars are fusion powerhouses; their gravity creates the perfect conditions for a self-sustaining fusion reaction and they keep burning until all their fuel — those atoms — are used up.

This idea forms the basis of fusion reactors.

Building a unit that can artificially re-create the conditions within the sun would allow for an extremely green source of energy. Fusion doesn’t directly produce greenhouse gases, like carbon dioxide and methane, which contribute to global warming.

And critically, a fusion reactor also doesn’t have the downsides of nuclear fission, the splitting of atoms used in nuclear bombs and reactors today.

In other words, a fusion power plant wouldn’t produce the radioactive waste associated with nuclear fission.

The big fusion experiment

The NIF, which takes up the space of around three football fields at LLNL, is the most powerful «inertial confinement fusion» experiment in the world.

In the center of the chamber lies a target: a «hohlraum,» or cylinder-shaped device that houses a tiny capsule. The capsule, about as big as a peppercorn, is filled with isotopes of hydrogen, deuterium and tritium, or D-T fuel, for short. The NIF focuses all 192 lasers at the target, creating extreme heat that produces plasma and kicks off an implosion. As a result, the D-T fuel is subject to extreme temperatures and pressures, fusing the hydrogen isotopes into helium — and a consequence of the reaction is a ton of extra energy and the release of neutrons.

You can think of this experiment as briefly simulating the conditions of a star.

The complicated part, though, is that the reaction also requires a ton of energy to start. Powering the entire laser system used by the NIF requires more than 400 megajoules — but only a small percentage actually hits the hohlraum with each firing of the beams. Previously, the NIF had been able to pretty consistently hit the target with around 2 megajoules from its lasers.

But on Dec. 5, during one run, something changed.

«Last week, for the first time, they designed this experiment so that the fusion fuel stayed hot enough, dense enough and round enough for long enough that it ignited,» Marv Adams, deputy administrator at the NNSA, said during the conference. «And it produced more energy than the lasers had deposited.»

More specifically, scientists at NIF kickstarted a fusion reaction using about 2 megajoules of energy to power the lasers and were able to get about 3 megajoules out. Based on the definition of ignition used by NIF, the benchmark has been passed during this one short pulse.

You might also see that energy gain in a fusion reaction is denoted by a variable, Q.

Like ignition, the Q value can refer to different things for different experiments. But here, it’s referring to the energy input from the lasers versus the energy output from the capsule. If Q = 1, scientists say they have achieved «breakeven,» where energy in equals energy out.

The Q value for this run, for context, was around 1.5.

In the grand scheme of things, the energy created with this Q value is only about enough to boil water in a kettle.

«The calculation of energy gain only considers the energy that hit the target, and not the [very large] energy consumption that goes into supporting the infrastructure,» said Patrick Burr, a nuclear engineer at the University of New South Wales.

The NIF is not the only facility chasing fusion — and inertial confinement is not the only way to kickstart the process. «The more common approach is magnetically confined fusion,» said Richard Garrett, senior advisor on strategic projects at the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organization. These reactors use magnetic fields to control the fusion reaction in a gas, typically in a giant, hollow donut reactor known as a tokamak.

Those devices have a much lower density than NIF’s pellets, so temperatures need to be increased to well over 100 million degrees. Garrett said he does not expect the NIF result to accelerate tokamak fusion programs because, fundamentally, the two processes work quite differently.

However, significant progress is also being made with magnetically confined fusion. For instance, the ITER experiment, under construction in France, uses a tokamak and is expected to begin testing in the next decade. It has lofty goals, aiming to achieve a Q greater than 10 and to develop commercial fusion by 2050.

The future of fusion

The experiment at NIF might be transformative for research, but it won’t immediately translate to a fusion energy revolution. This isn’t a power-generating experiment. It’s a proof of concept.

This is a point worth paying attention to today, especially as fusion has often been touted as a way to combat the climate crisis and reduce reliance on fossil fuels or as a salve for the world’s energy problems. Construction and utilization of fusion energy to power homes and businesses is still a ways off — decades, conservatively — and inherently reliant on technological improvements and investment in alternative energy sources.

Generating around 2.5 megajoules of energy when the total input from the laser system is well above 400 megajoules is, of course, not efficient. And in the case of the NIF experiment, it was one short pulse.

Looking further ahead, constant, reliable, long pulses will be required if this is to become sustainable enough to power kettles, homes or entire cities.

«It’s unlikely that fusion power … will save us from climate change,» said Ken Baldwin, a physicist at the Australian National University. If we are to prevent the largest increases in global average temperature, fusion power is likely going to be a little too late.

Other investment is going to come from private companies, which are seeking to operate tokamak fusion reactors in the next few years. For instance, Tokamak Energy in the UK is building a spherical tokamak reactor and seeks to hit breakeven by the middle of this decade.

Then there’s Commonwealth Fusion Systems, spun out of MIT, which is hoping to generate around 400 megawatts of power, enough for tens of thousands of homes, by the 2030s. Modern nuclear power plants can produce almost three times as much.

And as CNET editor Stephen Shankland noted in a recent piece, fusion reactors will also need to compete against solar and wind power — so even with today’s revelatory findings, fusion energy remains entrenched in the experimental phase of its existence.

But we can now cast one eye toward the future.

It may not prevent the worst of climate change but, harnessed to its full potential, it could produce a near-limitless supply of energy for generations to come. It’s one thing to think about the future of energy on Earth and how it will be utilized, but our eyes may fall on horizons even further out — deep space travel could utilize fusion reactors that blast us well beyond the reaches of our sun’s gravity, the very thing that helped teach us about fusion reactions, and into interstellar space.

Perhaps then, we’d remember Dec. 5, 2022, as the first tiny step toward places we dared once only dream about.

Correction, 8:44 a.m. PT: This article initially misstated the amount of energy in the fusion reaction. NIF powered the lasers with about 2 megajoules and produced 3 megajoules as a result.

Technologies

AI Agents at Work: Microsoft Copilot Is Getting Its Own Version of Claude Cowork

Built in collaboration with Anthropic, Microsoft’s new tool can create spreadsheets, run reports and do research autonomously.

Microsoft Copilot probably isn’t something you think about a lot, unless your company pays for you to use it at work. Microsoft has been fighting for consumers whose hearts and minds were quickly captured by other AI tools like ChatGPT and Gemini. The company’s latest wave of agentic updates, announced Monday, is its sharpest weapon yet.

The biggest new feature is Copilot Cowork, built in collaboration with Anthropic. If you’ve heard of or used Anthropic’s Claude Cowork, Microsoft’s version will feel similar. Copilot Cowork can use information in your files, email and calendar to independently complete assignments, no human supervision needed. It can create spreadsheets, run reports and do research for you.

«Cowork is the new chat. It’s the new way of interacting with AI,» said Charles Lamanna, Microsoft president of business apps and agents. Instead of overseeing AI and chatting with it, we can now entirely delegate tasks to it like a fellow team member. «With chat, you’re babysitting every step — this is much more like ‘fire and forget’ with Cowork to get the job done.»

For example, Lamanna said he used Cowork to analyze his meeting calendar for the next three months. The AI used his email and calendar history to understand what upcoming meetings may not be necessary for him to attend, and it pulled together its recommendations in an easy-to-view chart. After Lamanna reviewed it, Cowork declined some meetings, with AI-written meeting notes attached if needed. The AI’s 40-minute «delightful and practical» process saved him and his executive assistant hours worth of time so they could focus on more important duties.

Cowork is rolling out now on a limited basis as it’s a research preview concept. Microsoft also announced it will be making its AI agent platform, Agent 365, generally available on May 1. Agent 365 is a way for companies to oversee and manage all of the agents, or bots, that employees are using for their work. Microsoft itself has created more than a half-million AI agents using Agent 365, the company shared in a statement. New AI models from Anthropic and OpenAI will also be made available in Copilot. Smartly, the company isn’t picking a side in the growing feud between the AI startups.

Read More: AI Isn’t Human and We Need to Stop Treating It That Way, Says Microsoft AI CEO

Agentic AI at work

Agentic AI tools like the ones Microsoft is building are extremely popular for workers. Despite only being a research preview, Claude Cowork has garnered a lot of fans — and sparked a lot of worry on Wall Street. Major tech stocks fell at the end of January as Anthropic’s AI developments cast doubts on the future of work.

New AI tools like Cowork, Claude Code and even OpenAI’s Codex are becoming increasingly capable of replacing traditional software products, like the kind Microsoft is known for. So it makes sense that Microsoft would want to bring that agentic prowess to its own AI. Agentic AI has been a major area of focus for AI companies recently. OpenClaw, an open source agentic project that went viral this year, is one of many examples of why tech execs think 2026 will be the year of agentic AI.

Lamanna said that «the shape of what we do on a day-to-day basis will change,» but AI ought to give time back to people to focus on high-value tasks. We’re entering a new arc, going from having a human use AI to do a task quicker to delegating it entirely to an AI agent, he said.

As this tech becomes more available, there are a lot of questions about the best way to integrate AI into our work lives. Many workers are worried about having their jobs replaced by AI, fueled by AI-centric layoffs at Amazon and Block. For those who manage to keep their jobs, one study found that AI may actually make their work days longer and less enjoyable. Like any new tech, the implementation of AI will determine how effective it is — and how much it actually helps you.

Technologies

My iPhone 17E Review in Progress: The Appeal Is Magnetic (and Pink)

Apple’s new $599 budget phone brings MagSafe compatibility, higher base storage and an A19 chip. That makes the trade-offs easier to swallow.

I never thought MagSafe’s haptic feedback could be so satisfying.

I’ve been using Apple’s $599 iPhone 17E, which brings MagSafe’s magnetic technology to its lowest-priced handset. Beyond the added convenience of easily attaching chargers and accessories, this signals Apple’s efforts to expand once-premium features across its full iPhone lineup, no matter how much you’re willing to pay. Plus, the addition of a fresh color warms my pink-loving heart.

The iPhone 17E borrows other features from the $829 baseline iPhone 17. The budget option packs the same A19 chip (albeit with a four-core GPU instead of five), an action button and a 48-megapixel main camera. It starts with 256GB of storage, making that $599 price more enticing — even if it’s arguably pushing the limits of what’s considered a «budget» phone. But the fact that I have to double-check whether I’m reaching for the iPhone 17E or the 17 is surely a good sign that the gap between the two is narrowing — and in the right direction.

Other aspects of the 17E serve as a reminder that you get what you pay for. The bezels are noticeably thicker than on Apple’s more premium options. There’s no Dynamic Island for system notifications and Live Activities, but rather an old-school notch at the top. A fixed 60 Hz display also means there’s no always-on display, so I can’t quickly glance at the time or my notifications — something that’s been hard to get used to.

There’s a lot that makes the iPhone 17E feel like a worthy lower-priced option. And for most people, the compromises shouldn’t feel too glaring, especially when you’re saving a couple hundred dollars.

The iPhone 17E is available to preorder now, and hits store shelves on March 11.

iPhone 17E look, feel and display

One of my favorite things about the iPhone 17E is that it doesn’t sacrifice the premium look and feel of its pricier counterparts. Like the other iPhone 17 models, the iPhone 17E’s back glass has a satisfying matte finish that’s resistant to fingerprints. An aluminum frame keeps it feeling nice and light at 169 grams, compared to 177 grams on the iPhone 17.

The iPhone 17E’s 6.1-inch display is just slightly smaller than the 6.3-inch display on the iPhone 17, a difference that’s hardly noticeable. The lower-priced option shares the same Ceramic Shield 2 cover glass, which Apple says has three times better scratch resistance than the iPhone 16E’s display, and 33% less reflection.

The 60Hz refresh rate is a step down from the 1-120Hz adaptive refresh rate you’ll get on Apple’s other phones, but it’s a nearly imperceptible difference unless you’re gaming. Personally, the biggest downside to this limitation is not having an always-on display, which I rely on extensively to peek at the time and see all my notifications at a glance. Going without that feature has taken some getting used to.

While the iPhone 17 supports 1,600 nits HDR peak brightness, the iPhone 17E tops out at 1,200 nits peak HDR brightness. Holding the phones side by side, I can see the difference, but the 17E looks just fine, even in the California sunshine.

The iPhone 17E’s smaller size can either be a benefit or a drawback, depending on your preferences. I tend to gravitate toward larger phones, so typing and scrolling on a smaller frame was a bit of an adjustment. But if you want a more compact device that’ll fit in practically any pocket, you’ll dig the 17E’s dimensions.

This year, Apple decided to branch out and add a soft pink color option to its budget line, along with the standard black and white. Luckily, I got paired with a pink model that takes on a pastel-like, blush hue that’s certainly more subdued than the bold orange of the iPhone 17 Pro. The subtle shade is nice if you want some color without making too much of a statement. I’m always happy when fun colors aren’t limited to the pricier models.

iPhone 17E camera gets some minor upgrades

Similar to last year’s budget iPhone, the iPhone 17E has a single 48-megapixel rear camera. With sensor cropping, it can also snap 2x telephoto images, which look as good as 1x photos to my eyes. A bonus perk of having just one rear camera is that it’s significantly less obtrusive than the camera bumps on other iPhone 17 models, particularly the Pros. It’s refreshing to go back to a phone I can hold without my fingers brushing against an ever-expanding camera platform.

Like my experience with the iPhone Air, the lack of an ultrawide camera feels limiting. It’s harder to take landscape photos or capture a wider scene — though if I had to choose between an ultrawide and a telephoto camera, I’d always pick the latter. I’m much more likely to punch into something to show more detail than take a dramatically wider shot.

The iPhone 17E has a 12-megapixel selfie camera, drawing another parallel to the iPhone 16E. The 17E doesn’t get the Center Stage camera feature that debuted on the iPhone Air and 17, which can automatically switch between portrait and landscape orientation as more people come into the frame without you rotating your phone. I don’t see this as much of a loss; in fact, I keep Center Stage disabled on my iPhone 17 Pro Max, largely because old habits die hard and I just end up rotating my phone manually anyway.

Not having Cinematic mode for video on the budget line is still a bummer, since I rely on it for more professional-looking clips with blurred backgrounds. But if trade-offs have to be made, that’s a manageable one.

The hardware feature I’ve struggled without is the Camera Control button — not because I ever use it as a shortcut to Apple’s Visual Intelligence, but because that’s how I almost exclusively launch the iPhone’s camera now. I like having a physical button that’s easy to trigger (perhaps too easy for some) when I want to quickly snap a photo. Without Camera Control on the iPhone 17E, you’ll have to open the camera the old-fashioned way by tapping on your screen, swiping the lock screen to the left or using the action button as a camera shortcut. Though I don’t think most people will mind that, especially if you’re coming from a phone that never had Camera Control in the first place. And you can access Visual Intelligence from the iPhone 17E’s Control Panel.

Portraits get a nice boost on the iPhone 17E, compared to last year’s budget phone. Apple says the advanced image pipeline allows subjects to stand out more naturally against their bokeh-effect backgrounds. For example, a person will appear in sharper focus, including fringe details like their hair or the corner of their glasses, and the transition to the image’s blurred background looks a bit more gradual and realistic.

When you’re snapping pictures in the camera’s standard Photo mode, it’ll now automatically detect cats and dogs, in addition to people, and enable portrait shots without you having to switch to that setting.

And now, you can also adjust the focus point of a photo after you’ve snapped it by going to Edit in the Photos app and tapping where you want to focus. You can modify the amount of background blur, too. It’s great to see that flexibility and customization on Apple’s lower-tier phone.

Here are a few of my favorite photos I’ve taken on the iPhone 17E:

iPhone 17E battery and MagSafe compatibility

The iPhone 17E touts the same 26 hours of video playback as the iPhone 16E. On Apple’s product pages in the European Union, where it’s required to disclose battery capacity, that’s listed as 4,005 mAh, (the same as the 16E). Apple says the battery is aided by the power-efficient A19 chip, the new C1X cellular modem and the «advanced power management of iOS 26.»

In my first few days with the phone, the battery has held up impressively well. I started with a full battery at 10:12 a.m. on Saturday, and still had a healthy 48% by 8 p.m. When I woke up the next morning at 5:15 a.m. (yes, my sleep schedule has been completely thrown off by Mobile World Congress and jet lag), the phone was at 38%. I feel confident I can go about my day without worrying about the phone dying prematurely.

The iPhone 17E supports 20-watt wired charging. And with MagSafe and Qi2 compatibility, it can charge wirelessly up to 15 watts — double the 7.5 watts on the iPhone 16E. That’s still less than the 25-watt wireless charging (Qi2.2) the iPhone 17 supports, but it’s a worthy step up from last year.

With wired charging, the iPhone 17E went from 8% to 61% in half an hour. I look forward to testing MagSafe charging speeds as well.

I’ve enjoyed snapping MagSafe accessories such as cases and wallets onto the iPhone 17E simply because I can. I’ve also been tapping into Apple’s StandBy feature, which displays widgets while you charge your phone in landscape mode, including a calendar, clock and photos.

Final thoughts for now: Should you buy the iPhone 17E?

The iPhone 17E brings subtle yet welcome changes to Apple’s budget line — namely, MagSafe charging, a higher base storage level and a more advanced A19 chip. This year’s phone shares a lot in common with the iPhone 16E, especially when it comes to the cameras and battery capacity, but it still shines in both areas.

More notably, the iPhone 17E borrows a handful of features from the baseline iPhone 17, which costs $200 more. The phones have a similar feel, a 48-megapixel main camera and that A19 chip. You’ll spot some notable design differences, including the iPhone 17E’s prominent notch, wider bezels and the lack of a Camera Control button.

If you’re switching from an older iPhone like the iPhone 11 or 12, these are trade-offs you’ll hardly notice, especially in light of all the relative upgrades. Similarly, if you’re coming from another budget phone that’s a few years old, like the iPhone SE (2020) or an older Android counterpart, the improvements are sure to outweigh any missing premium features.

If you’re using last year’s iPhone 16E, the incremental changes don’t justify the upgrade, even with the long-awaited addition of MagSafe. Apple doesn’t appear to be targeting this demographic anyway, since its promotional materials largely compare the iPhone 17E to older models like the iPhone 11. That’s where the differences really stand out.

Apple iPhone 17E specs vs. Google Pixel 10A, Apple iPhone 17, Apple iPhone 16E

| Apple iPhone 17E | Google Pixel 10A | Apple iPhone 17 | Apple iPhone 16E | |

| Display size, tech, resolution, refresh rate | 6.1-inch OLED display; 2,532×1,170 pixels; 60Hz refresh rate | 6.3-inch POLED, 2,424×1,080 pixels, 60-120Hz variable refresh rate | 6.3-inch OLED; 2,622×1,206 pixels; 1-120Hz variable refresh rate | 6.1-inch OLED display; 2,532×1,170 pixels; 60Hz refresh rate |

| Pixel density | 460 ppi | 422 ppi | 460 ppi | 460 ppi |

| Dimensions (inches) | 5.78×2.82×0.31 | 6.1×2.9×0.4 | 5.89×2.81×0.31 | 5.78×2.82×0.31 |

| Dimensions (millimeters) | 146.7×71.5×7.8 | 154.7×73.3×8.9 | 149.6×71.5×7.95 | 146.7×71.5×7.8 |

| Weight (grams, ounces) | 167g (5.88 oz.) | 183 g (6.5 oz) | 177g (6.24 oz.) | 167g (5.88 oz.) |

| Mobile software | iOS 26 | Android 16 | iOS 26 | iOS 18 |

| Camera | 48-megapixel (wide) | 48-megapixel (wide), 13-megapixel (ultrawide) | 48-megapixel (wide) 48-megapixel (ultrawide) | 48-megapixel (wide) |

| Front-facing camera | 12-megapixel | 13-megapixel | 18-megapixel | 12-megapixel |

| Video capture | 4K | 4K | 4K | 4K |

| Processor | Apple A19 | Google Tensor G4 | Apple A19 | Apple A18 |

| RAM + storage | RAM unknown + 256GB, 512GB | 8GB + 128GB, 256GB | RAM N/A + 256GB, 512GB | RAM unknown + 128GB, 256GB, 512GB |

| Expandable storage | None | None | None | None |

| Battery | 4,005 mAh | 5,100 mAh | 3,692 mAh | 4,005 mAh |

| Fingerprint sensor | None, Face ID | Under display | None, Face ID | None, Face ID |

| Connector | USB-C | USB-C | USB-C | USB-C |

| Headphone jack | None | None | None | None |

| Special features | MagSafe, Qi2 charging (up to 15W), Action button, Apple C1 5G modem, Apple Intelligence, Ceramic Shield, Emergency SOS, satellite connectivity, IP68 resistance | 7 years of OS, security and Pixel feature drops, Gorilla Glass 3 cover glass, IP68 dust and water resistance, 3,000-nit peak brightness, 2,000,000:1 contrast ratio, 30W fast charging with 45W charging adapter (charger not included), 10W wireless charging Qi certified, Satellite SOS, Wi-Fi 6E, NFC, Bluetooth 6, dual-SIM (nano SIM + eSIM), Camera Coach, Add Me, Best Take, Magic Eraser, Magic Editor, Photo Unblur, Super Res Zoom, Circle to Search; colors: lavender, berry, fog, obsidian (black) | Apple N1 wireless networking chip: Wi-Fi 7 (802.11be) with 2×2 MIMO, Bluetooth 6, Thread, Action button, Camera Control button, Dynamic Island, Apple Intelligence, Visual Intelligence, dual eSIM, 1 to 3,000 nits brightness display range, IP68 resistance; colors: black, white, mist blue, sage, lavender; fast charge up to 50% in 20 minutes using 40W adapter or higher via charging cable; fast charge up to 50% in 30 minutes using 30W adapter or higher via MagSafe Charger | Action button, Apple C1 5G modem, Apple Intelligence, Ceramic Shield, Emergency SOS, satellite connectivity, IP68 resistance |

| US price starts at | $599 (256GB) | $500 (128GB) | $829 (256GB) | $599 (128GB) |

Technologies

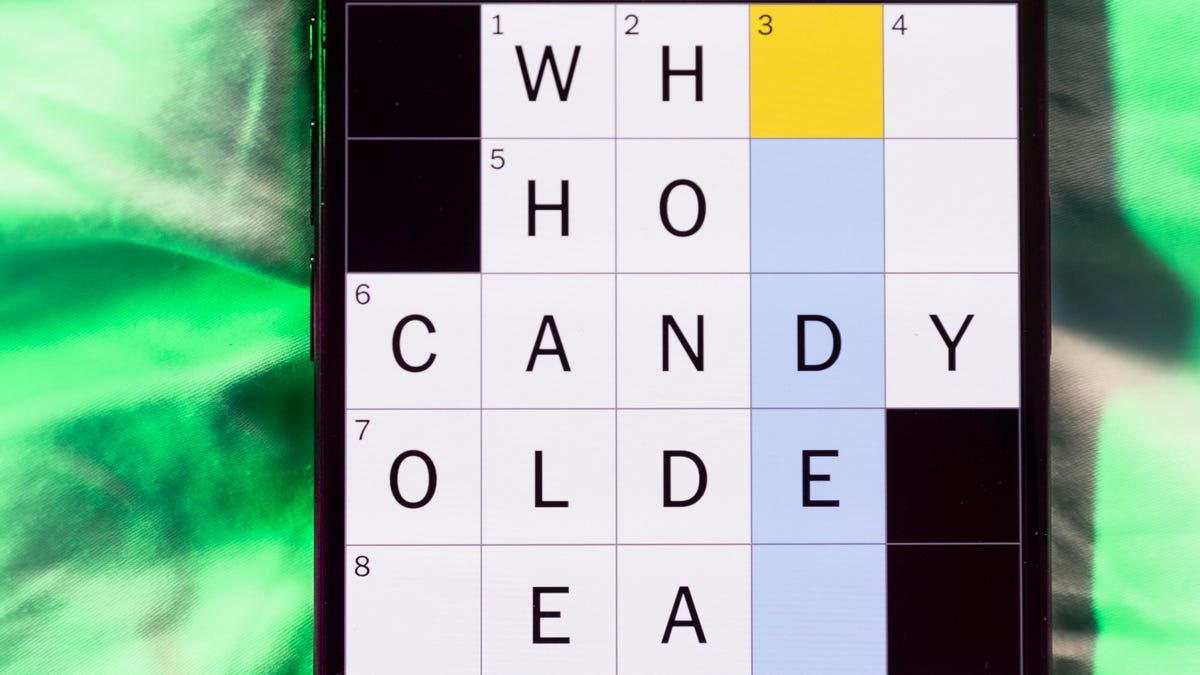

Today’s NYT Mini Crossword Answers for Monday, March 9

Here are the answers for The New York Times Mini Crossword for March 9.

Looking for the most recent Mini Crossword answer? Click here for today’s Mini Crossword hints, as well as our daily answers and hints for The New York Times Wordle, Strands, Connections and Connections: Sports Edition puzzles.

Need some help with today’s Mini Crossword? Read on for all the answers. And if you could use some hints and guidance for daily solving, check out our Mini Crossword tips.

If you’re looking for today’s Wordle, Connections, Connections: Sports Edition and Strands answers, you can visit CNET’s NYT puzzle hints page.

Read more: Tips and Tricks for Solving The New York Times Mini Crossword

Let’s get to those Mini Crossword clues and answers.

Mini across clues and answers

1A clue: Talk ___ (boastfully banter)

Answer: SMACK

6A clue: What has legs, but never walks?

Answer: TABLE

7A clue: French for «love»

Answer: AMOUR

8A clue: What has a mouth, but never talks?

Answer: RIVER

9A clue: Run-down in appearance

Answer: SEEDY

Mini down clues and answers

1D clue: Milky Way bits

Answer: STARS

2D clue: ___ Eisenhower, 1950s first lady

Answer: MAMIE

3D clue: Overhead

Answer: ABOVE

4D clue: Given a crossword hint

Answer: CLUED

5D clue: Actress Washington of «Scandal»

Answer: KERRY

-

Technologies3 года ago

Technologies3 года agoTech Companies Need to Be Held Accountable for Security, Experts Say

-

Technologies3 года ago

Technologies3 года agoBest Handheld Game Console in 2023

-

Technologies3 года ago

Technologies3 года agoTighten Up Your VR Game With the Best Head Straps for Quest 2

-

Technologies4 года ago

Technologies4 года agoBlack Friday 2021: The best deals on TVs, headphones, kitchenware, and more

-

Technologies5 лет ago

Technologies5 лет agoGoogle to require vaccinations as Silicon Valley rethinks return-to-office policies

-

Technologies5 лет ago

Technologies5 лет agoVerum, Wickr and Threema: next generation secured messengers

-

Technologies4 года ago

Technologies4 года agoOlivia Harlan Dekker for Verum Messenger

-

Technologies4 года ago

Technologies4 года agoiPhone 13 event: How to watch Apple’s big announcement tomorrow