Technologies

Analogue 3D Review: The Purest Nintendo 64 Experience You Can Have on a 4K TV

There are plenty of ways to play Nintendo 64 games in 2025. The Analogue 3D is made for purists.

Pros

- Perfect playback

- Incredible sound reproduction

- Beautiful design

- Competitively priced

- Overclocking

Cons

- Wireless controllers need direct line-of-sight

- Barebones UI

- Missing screenshot feature

- No Wi-Fi

- Doesn’t support flash carts

As a kid, my parents promised to buy me a Nintendo 64 if I brought home straight A’s on my report card. I was having trouble staying motivated in class, but playing Mario Kart 64 at my cousin’s house lit a fire under me, one that was in awe of speed-boosting mushrooms and spiny blue shells. I’d never experienced anything like it, and I wanted it for myself.

I didn’t get the Nintendo 64. I ended up depositing my report card console credit for a Sega Dreamcast instead, lured by a gory late-night commercial for Sonic Adventure 2.

In the 25 years since then, I’ve wondered how my gaming journey would have evolved if I’d opted for the Nintendo 64. Instead of my childhood being defined by Crazy Taxi and Jet Grind Radio, it’d have been marked by the tunes of Kokiri Forest from the Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time or the accordions of Cool, Cool Mountain in Super Mario 64. I’d certainly be listening to less of The Offspring.

Luckily for myself and others like me, Analogue, the retro video game company known for releasing modern versions of old-school consoles, believes it’s time for the Nintendo 64 to make a comeback. In creating the Analogue 3D, as the new console is called, the company shuns the corners cut by all the knock-off emulation handhelds flooding AliExpress and TikTok Shop in its aim for absolute purity.

The Nintendo 64 was Nintendo’s third at-home video game console (if you don’t count the Japan-only Color TV-Game), and the first to go all-in on 3D. Despite commendations from gamers for its genre-defining titles, it wasn’t a tremendous seller, with only 32.93 million units sold worldwide. By comparison, the original Nintendo Entertainment System sold 61 million units, and the Wii sold 101 million. The highest-selling Nintendo home console is the Switch, which sits at 154 million machines sold to date. But it looms large in the minds of Millennial gamers like myself as the technological turning point when Mario and other iconic characters made the leap to 3D.

In the years since the Nintendo 64 was surpassed by newer, more advanced consoles, most gamers wanting to get back into N64 gaming have had to do so either by finding old systems at garage sales, downloading emulators or playing titles via the Nintendo Switch Online service. Each of these methods has specific drawbacks, from availability to compatibility with today’s 4K TVs, making it difficult to find the definitive Nintendo 64 experience in 2025.

The Analogue 3D aims to solve the conundrum of playing N64 games — from the cartridges themselves, if desired — on modern televisions, just as modders have been finding new ways to make old hardware work with today’s TVs. Products like the N64 HDMI Retro GEM modify an existing Nintendo 64 by inserting native HDMI output and scaling the signal for higher-resolution screens. This mod bypasses the need for flimsy composite-to-HDMI video adapters or other expensive scaling devices while also delivering a pure digital video signal. The problem is that at $210, the kit is expensive and requires intermediate-level soldering.

By contrast, the Analogue 3D is ready to go out of the box, natively supports HDMI output and internal scaling and forgoes the need to make risky modifications to an old console. And at $250, Analogue’s device is a clean, headache-free, competitively priced all-in-one solution. It also includes a wireless controller. Although ModRetro, which released the Chromatic Game Boy handheld earlier this year, is working on its own modern Nintendo 64 and says it’ll be priced at $200.

Like past Analogue devices, the Analogue 3D has a clean design that evokes the refinement and sophistication of an Apple product. But in an era where playing N64 games can be done with little hassle via software emulators, the Analogue 3D will appeal to only the most hard-core of retro enthusiasts – or those that don’t want to fiddle with installing apps and hunting down ROMs via dubious websites.

4K Nintendo 64 sounds awesome but turns into a blocky mess

The Analogue 3D is easy to use. It quickly boots up, and the UI, while spartan, cleanly displays your collection of games and plays them as intended.

The 3D uses FPGA technology to re-create the original system’s hardware, down to the transistor level. This means when you plug in an old N64 cartridge, the new console runs the code as originally intended. There’s no software emulation here. The images you see and the sounds you hear are unfiltered, which, for purists, is the ultimate expression of their chunky gray cartridges that have been lying dormant for the past 30 years.

Because there is no software trickery, you can’t leverage some features found in software emulators. The in-game models in Mario Kart 64 still retain the same blocky pixels, whereas Project64, a popular open-source N64 emulator, can internally render games at higher resolutions, which makes the textures and geometry look sharper and clearer. There are other enhancements that users can implement to make the image look cleaner. Fans have also made 4K texture packs that make the 29-year-old kart racer look as if it were made for modern systems.

While the raw, unfiltered image coming out of the Analogue 3D might not compare with what software emulation can achieve, it does include a slew of filters.

Video game hardware from the 1990s and 2000s was made to work with televisions of that era. The N64’s original 320×240-pixel video output was designed to scale on lower-resolution TVs that had scanlines running across them. This softened the image and helped blur the jagged pixels. Analogue has included multiple filters and scaling solutions that faithfully showcase N64 games as they were meant to be seen. On-board filters can simulate the screens of broadcast video monitors, production video monitors and cathode ray tube televisions. I personally prefer the image from BVM or PVM.

This, I feel, is where the divide will lie between purists and emulation enthusiasts. The purist doesn’t want to play with a clean, unfiltered image and prefers some kind of filter that portrays N64 games on the medium they were originally intended for. For those who grew up with emulation, however, they might prefer the cleaner upscaled image, which presents better on modern televisions and displays. For this latter group, sticking to Project64 or Nintendo Switch Online might be the more ideal option.

N64 emulation on Nintendo Switch can’t match the Analogue 3D’s sound

In jumping back and forth between my copy of Mario Kart 64 on the Analogue 3D and the version available via Nintendo Switch Online, one thing that immediately struck me was the depth and richness of sound through the former solution.

When playing on the 3D, the music was fuller, and, to my surprise, had surround sound support. Bass had a pronounced umph and speakers reverberated tonal clarity that the Switch Online couldn’t match. Honestly, the N64 games available on Switch sounded meek in comparison.

When researching online, the N64 could output stereo audio (and Dolby Pro Logic surround) at 44.1kHz at 16-bit. This sample rate, however, was computationally expensive and games would often lower the audio quality as a result. The Analogue 3D can push audio out at 48kHz/16-bit PCM.

Analogue says it sourced high-quality HiFi components that cost dollars each, versus cheaper ones that only run a few cents. In springing for pricier parts, the company compared the console’s more impressive audio output to the difference between Spotify’s standard 128kbps playback to full-sound lossless audio formats. According to Analogue, its console is the first HiFi N64.

Considering how wildly better games sounded via the 3D, I’m inclined to believe Analogue.

Lowest latency

Input latency has long plagued N64 software emulation. It’s a problem that Nintendo itself ran into when it added N64 games to its Nintendo Switch Online service (along with a slew of other issues). Since the Analogue 3D isn’t doing software emulation, input latency is virtually non-existent.

When playing Mario Kart or Super Smash Bros., input quality was generally fast via the included 8BitDo 64 Bluetooth Controller. We didn’t have an original wired N64 controller on hand to test wired input.

Oddly, it seems that the Analogue 3D itself needs a clear line of sight with a connected controller, or else it’ll lag badly. I’m unsure why this is, but prospective buyers should make sure that the 3D is clearly visible under their television or else they’ll run into issues.

Yes, the Analogue 3D overclocks

Toward the end of the Nintendo 64 lifecycle, a few games were released that really pushed the original hardware. This includes iconic titles like Perfect Dark, Donkey Kong 64 and Conker’s Bad Fur Day. For our testing, we didn’t have access to these games. But the Analogue 3D does have overclock options to eke out some extra horsepower for smoother gameplay.

This technically isn’t cheating on Analogue’s part. Nintendo actually sent out more powerful development kits to developers toward the end of the N64 lifecycle, according to Analogue. Some of these games never came to light, but some titles did suffer from choppy framerates as a result.

The games we had on hand weren’t as technically demanding. But upping the horsepower on the 3D on more visually complex tracks in Mario Kart, like Sherbet Land, played without issue.

PilotWings 64 is another game that had frame rate issues when it launched in 1996. The game itself runs at an uncapped frame rate. In our testing, the game was smooth when the 3D was in its experimental overclocked mode.

Sorry, no flash carts… yet?

Some Nintendo 64 games are expensive. Obscure titles like Clay Fighters and Super Bowling can cost north of $500 on eBay or other online secondary markets. More in-demand titles with greater availability, like The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask and Pokemon Stadium 2, can run for between $40 and $60. Unless you’re already sitting on a decent N64 collection, getting the most out of an Analogue 3D will cost money.

Over the years, however, flash cartridges have emerged, letting gamers load dumped ROMs onto a single cartridge via an SD card. This allows one cartridge to be able to play an entire library of backed-up titles. The Everdrive 64 X7, made by Ukrainian developer Krikzz, is considered to be the gold standard of N64 flashcarts. However, unofficial cartridges don’t work with the Analogue 3D.

Analogue documentation says it’s up to the vendor to allow for Analogue 3D support. When contacted, Krikzz support said Analogue didn’t reach out regarding compatibility and isn’t sure why the Everdrive 64 X7 isn’t working, but he hopes to get it figured out soon.

No regrets

Even though it had a short life, the Sega Dreamcast was an awesome video game system. I don’t regret getting it over the N64. Sure, it didn’t feature Mario or Zelda, but it did offer memorable experiences that shaped my video game journey.

Over the years, I have been able to play many of the Nintendo 64’s best titles, most of which were ported to subsequent Nintendo systems. But those ports sometimes came with odd quirks and compromises. The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask 3D for the Nintendo 3DS apparently had some odd jump timing, which made traversing the game more of a hassle. It was also less challenging. This is an instance where I’d like to hunt down an original N64 version of the game and play it as it was originally designed.

Given the overall quality, I do believe the Analogue 3D is worth the $250 price tag. I don’t think it’ll appeal to all buyers, however. There will be a contingent of gamers who will be content with playing the handful of titles via Nintendo Switch Online or through an emulator on their computer. Given the level of enhancements available on the emulation side of things via modders, it might even be better. The Analogue 3D is specifically catered toward purists, those who want to play on original hardware. For this reviewer, there really isn’t anything else like the Analogue 3D. Well, not yet.

While I didn’t get to extensively experience the Nintendo 64 as a kid, the Analogue 3D is giving me back what I missed out on. And in that sense, given how good the new 3D console is, maybe opting to get a Dreamcast back in 2001 gave me the opportunity to experience N64 games at their best — even if it took a few decades.

Technologies

AI Slop Is Destroying the Internet. These Are the People Fighting to Save It

Technologies

The Sun’s Temper Tantrums: What You Should Know About Solar Storms

Solar storms are associated with the lovely aurora borealis, but they can have negative impacts, too.

Last month, Earth was treated to a massive aurora borealis that reached as far south as Texas. The event was attributed to a solar storm that lasted nearly a full day and will likely contend for the strongest of 2026. Such solar storms are usually fun for people on Earth, as we are protected from solar radiation by our planet’s atmosphere, so we can just enjoy the gorgeous greens and pretty purples in the night sky.

But solar storms are a lot more than just the aurora borealis we see, and sometimes they can cause real damage. There are several examples of this in recorded history, with the earliest being the Carrington Event, a solar storm that took place on Sept. 1, 1859. It remains the strongest solar storm ever recorded, where the world’s telegraph machines became overloaded with energy from it, causing them to shock their operators, send ghost messages and even catch on fire.

Things have changed a lot since the mid-1800s, and while today’s technology is a lot more resistant to solar radiation than it once was, a solar storm of that magnitude could still cause a lot of damage.

What is a solar storm?

A solar storm is a catchall term that describes any disturbance in the sun that involves the violent ejection of solar material into space. This can come in the form of coronal mass ejections, where clouds of plasma are ejected from the sun, or solar flares, which are concentrated bursts of electromagnetic radiation (aka light).

A sizable percentage of solar storms don’t hit Earth, and the sun is always belching material into space, so minor solar storms are quite common. The only ones humans tend to talk about are the bigger ones that do hit the Earth. When this happens, it causes geomagnetic storms, where solar material interacts with the Earth’s magnetic fields, and the excitations can cause issues in everything from the power grid to satellite functionality. It’s not unusual to hear «solar storm» and «geomagnetic storm» used interchangeably, since solar storms cause geomagnetic storms.

Solar storms ebb and flow on an 11-year cycle known as the solar cycle. NASA scientists announced that the sun was at the peak of its most recent 11-year cycle in 2024, and, as such, solar storms have been more frequent. The sun will metaphorically chill out over time, and fewer solar storms will happen until the cycle repeats.

This cycle has been stable for hundreds of millions of years and was first observed in the 18th century by astronomer Christian Horrebow.

How strong can a solar storm get?

The Carrington Event is a standout example of just how strong a solar storm can be, and such events are exceedingly rare. A rating system didn’t exist back then, but it would have certainly maxed out on every chart that science has today.

We currently gauge solar storm strength on four different scales.

The first rating that a solar storm gets is for the material belched out of the sun. Solar flares are graded using the Solar Flare Classification System, a logarithmic intensity scale that starts with B-class at the lowest end, and then increases to C, M and finally X-class at the strongest. According to NASA, the scale goes up indefinitely and tends to get finicky at higher levels. The strongest solar flare measured was in 2003, and it overloaded the sensors at X17 and was eventually estimated to be an X45-class flare.

CMEs don’t have a named measuring system, but are monitored by satellites and measured based on the impact they have on the Earth’s geomagnetic field.

Once the material hits Earth, NOAA uses three other scales to determine how strong the storm was and which systems it may impact. They include:

- Geomagnetic storm (G1-G5): This scale measures how much of an impact the solar material is having on Earth’s geomagnetic field. Stronger storms can impact the power grid, electronics and voltage systems.

- Solar radiation storm (S1-S5): This measures the amount of solar radiation present, with stronger storms increasing exposure to astronauts in space and to people in high-flying aircraft. It also describes the storm’s impact on satellite functionality and radio communications.

- Radio blackouts (R1-R5): Less commonly used but still very important. A higher R-rating means a greater impact on GPS satellites and high-frequency radios, with the worst case being communication and navigation blackouts.

Solar storms also cause auroras by exciting the molecules in Earth’s atmosphere, which then light up as they «calm down,» per NASA. The strength and reach of the aurora generally correlate with the strength of the storm. G1 storms rarely cause an aurora to reach further south than Canada, while a G5 storm may be visible as far south as Texas and Florida. The next time you see a forecast calling for a big aurora, you can assume a big solar storm is on the way.

How dangerous is a solar storm?

The overwhelming majority of solar storms are harmless. Science has protections against the effects of solar storms that it did not have back when telegraphs were catching on fire, and most solar storms are small and don’t pose any threat to people on the surface since the Earth’s magnetic field protects us from the worst of it.

That isn’t to say that they pose no threats. Humans may be exposed to ionizing radiation (the bad kind of radiation) if flying at high altitudes, which includes astronauts in space. NOAA says that this can happen with an S2 or higher storm, although location is really important here. Flights that go over the polar caps during solar storms are far more susceptible than your standard trip from Chicago to Houston, and airliners have a whole host of rules to monitor space weather, reroute flights and monitor long-term radiation exposure for flight crews to minimize potential cancer risks.

Larger solar storms can knock quite a few systems out of whack. NASA says that powerful storms can impact satellites, cause radio blackouts, shut down communications, disrupt GPS and cause damaging power fluctuations in the power grid. That means everything from high-frequency radio to cellphone reception could be affected, depending on the severity.

A good example of this is the Halloween solar storms of 2003. A series of powerful solar flares hit Earth on Oct. 28-31, causing a solar storm so massive that loads of things went wrong. Most notably, airplane pilots had to change course and lower their altitudes due to the radiation wreaking havoc on their instruments, and roughly half of the world’s satellites were entirely lost for a few days.

A paper titled Flying Through Uncertainty was published about the Halloween storms and the troubles they caused. Researchers note that 59% of all satellites orbiting Earth at the time suffered some sort of malfunction, like random thrusters going offline and some shutting down entirely. Over half of the Earth’s satellites were lost for days, requiring around-the-clock work from NASA and other space agencies to get everything back online and located.

Earth hasn’t experienced a solar storm on the level of the Carrington Event since it occurred in 1859, so the maximum damage it could cause in modern times is unknown. The European Space Agency has run simulations, and spoiler alert, the results weren’t promising. A solar storm of that caliber has a high chance of causing damage to almost every satellite in orbit, which would cause a lot of problems here on Earth as well. There were also significant risks of electrical blackouts and damage. It would make one heck of an aurora, but you might have to wait to post it on social media until things came back online.

Do we have anything to worry about?

We’ve mentioned two massive solar storms with the Halloween storms and the Carrington Event. Such large storms tend to occur very infrequently. In fact, those two storms took place nearly 150 years apart. Those aren’t the strongest storms yet, though. The very worst that Earth has ever seen were what are known as Miyake events.

Miyake events are times throughout history when massive solar storms were thought to have occurred. These are measured by massive spikes in carbon-14 that were preserved in tree rings. Miyake events are few and far between, but science believes at least 15 such events have occurred over the past 15,000 years. That includes one in 12350 BCE, which may have been twice as large as any other known Miyake event.

They currently hold the title of the largest solar storms that we know of, and are thought to be caused by superflares and extreme solar events. If one of these happened today, especially one as large as the one in 12350 BCE, it would likely cause widespread, catastrophic damage and potentially threaten human life.

Those only appear to happen about once every several hundred to a couple thousand years, so it’s exceedingly unlikely that one is coming anytime soon. But solar storms on the level of the Halloween storms and the Carrington Event have happened in modern history, and humans have managed to survive them, so for the time being, there isn’t too much to worry about.

Technologies

TMR vs. Hall Effect Controllers: Battle of the Magnetic Sensing Tech

The magic of magnets tucked into your joysticks can put an end to drift. But which technology is superior?

Competitive gamers look for every advantage they can get, and that drive has spawned some of the zaniest gaming peripherals under the sun. There are plenty of hardware components that actually offer meaningful edges when implemented properly. Hall effect and TMR (tunnel magnetoresistance or tunneling magnetoresistance) sensors are two such technologies. Hall effect sensors have found their way into a wide variety of devices, including keyboards and gaming controllers, including some of our favorites like the GameSir Super Nova.

More recently, TMR sensors have started to appear in these devices as well. Is it a better technology for gaming? With multiple options vying for your lunch money, it’s worth understanding the differences to decide which is more worthy of living inside your next game controller or keyboard.

How Hall effect joysticks work

We’ve previously broken down the difference between Hall effect tech and traditional potentiometers in controller joysticks, but here’s a quick rundown on how Hall effect sensors work. A Hall effect joystick moves a magnet over a sensor circuit, and the magnetic field affects the circuit’s voltage. The sensor in the circuit measures these voltage shifts and maps them to controller inputs. Element14 has a lovely visual explanation of this effect here.

The advantage this tech has over potentiometer-based joysticks used in controllers for decades is that the magnet and sensor don’t need to make physical contact. There’s no rubbing action to slowly wear away and degrade the sensor. So, in theory, Hall effect joysticks should remain accurate for the long haul.

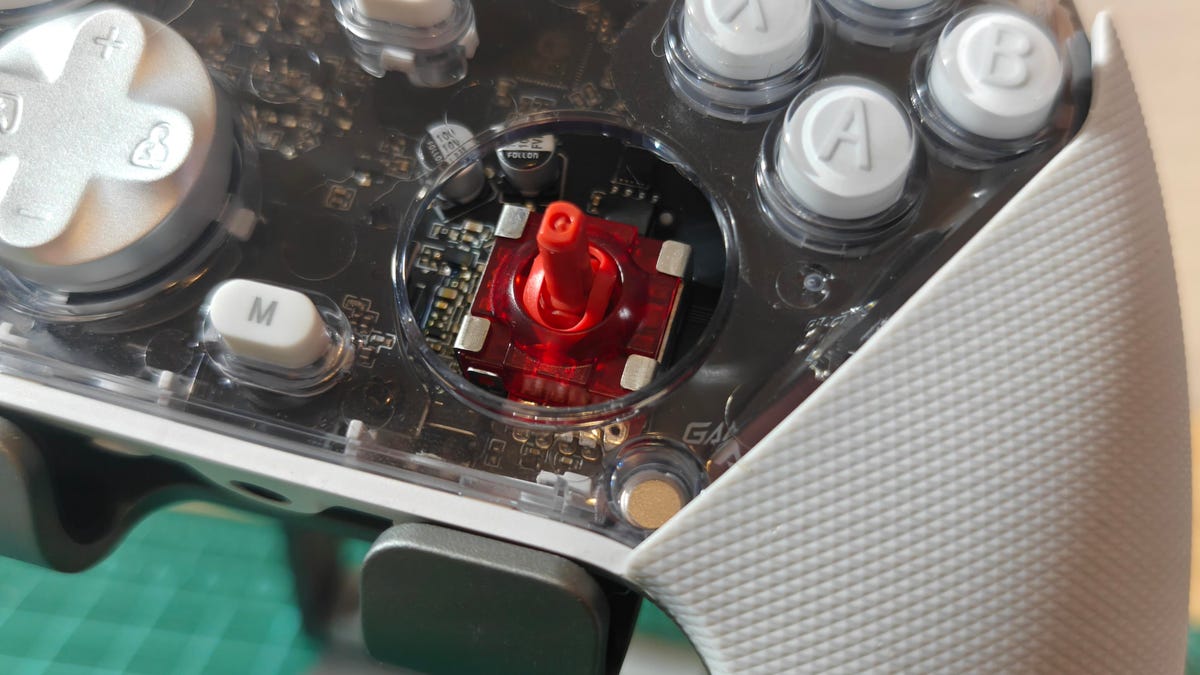

How TMR joysticks work

While TMR works differently, it’s a similar concept to Hall effect devices. When you move a TMR joystick, it moves a magnet in the vicinity of the sensor. So far, it’s the same, right? Except with TMR, this shifting magnetic field changes the resistance in the sensor instead of the voltage.

There’s a useful demonstration of a sensor in action here. Just like Hall effect joysticks, TMR joysticks don’t rely on physical contact to register inputs and therefore won’t suffer the wear and drift that affects potentiometer-based joysticks.

Which is better, Hall effect or TMR?

There’s no hard and fast answer to which technology is better. After all, the actual implementation of the technology and the hardware it’s built into can be just as important, if not more so. Both technologies can provide accurate sensing, and neither requires physical contact with the sensing chip, so both can be used for precise controls that won’t encounter stick drift. That said, there are some potential advantages to TMR.

According to Coto Technology, who, in fairness, make TMR sensors, they can be more sensitive, allowing for either greater precision or the use of smaller magnets. Since the Hall effect is subtler, it relies on amplification and ultimately requires extra power. While power requirements vary from sensor to sensor, GameSir claims its TMR joysticks use about one-tenth the power of mainstream Hall effect joysticks. Cherry is another brand highlighting the lower power consumption of TMR sensors, albeit in the brand’s keyboard switches.

The greater precision is an opportunity for TMR joysticks to come out ahead, but that will depend more on the controller itself than the technology. Strange response curves, a big dead zone (which shouldn’t be needed), or low polling rates could prevent a perfectly good TMR sensor from beating a comparable Hall effect sensor in a better optimized controller.

The power savings will likely be the advantage most of us really feel. While it won’t matter for wired controllers, power savings can go a long way for wireless ones. Take the Razer Wolverine V3 Pro, for instance, a Hall effect controller offering 20 hours of battery life from a 4.5-watt-hour battery with support for a 1,000Hz polling rate on a wireless connection. Razer also offers the Wolverine V3 Pro 8K PC, a near-identical controller with the same battery offering TMR sensors. They claim the TMR version can go for 36 hours on a charge, though that’s presumably before cranking it up to an 8,000Hz polling rate — something Razer possibly left off the Hall effect model because of power usage.

The disadvantage of the TMR sensor would be its cost, but it appears that it’s negligible when factored into the entire price of a controller. Both versions of the aforementioned Razer controller are $199. Both 8BitDo and GameSir have managed to stick them into reasonably priced controllers like the 8BitDo Ultimate 2, GameSir G7 Pro and GameSir Cyclone 2.

So which wins?

It seems TMR joysticks have all the advantages of Hall effect joysticks and then some, bringing better power efficiency that can help in wireless applications. The one big downside might be price, but from what we’ve seen right now, that doesn’t seem to be much of an issue. You can even find both technologies in controllers that cost less than some potentiometer models, like the Xbox Elite Series 2 controller.

Caveats to consider

For all the hype, neither Hall effect nor TMR joysticks are perfect. One of their key selling points is that they won’t experience stick drift, but there are still elements of the joystick that can wear down. The ring around the joystick can lose its smoothness. The stick material can wear down (ever tried to use a controller with the rubber worn off its joystick? It’s not pleasant). The linkages that hold the joystick upright and the springs that keep it stiff can loosen, degrade and fill with dust. All of these can impact the continued use of the joystick, even if the Hall effect or TMR sensor itself is in perfect operating order.

So you might not get stick drift from a bad sensor, but you could get stick drift from a stick that simply doesn’t return to its original resting position. That’s when having a controller that’s serviceable or has swappable parts, like the PDP Victrix Pro BFG, could matter just as much as having one with Hall effect or TMR joysticks.

-

Technologies3 года ago

Technologies3 года agoTech Companies Need to Be Held Accountable for Security, Experts Say

-

Technologies3 года ago

Technologies3 года agoBest Handheld Game Console in 2023

-

Technologies3 года ago

Technologies3 года agoTighten Up Your VR Game With the Best Head Straps for Quest 2

-

Technologies4 года ago

Technologies4 года agoBlack Friday 2021: The best deals on TVs, headphones, kitchenware, and more

-

Technologies5 лет ago

Technologies5 лет agoGoogle to require vaccinations as Silicon Valley rethinks return-to-office policies

-

Technologies5 лет ago

Technologies5 лет agoVerum, Wickr and Threema: next generation secured messengers

-

Technologies4 года ago

Technologies4 года agoOlivia Harlan Dekker for Verum Messenger

-

Technologies4 года ago

Technologies4 года agoiPhone 13 event: How to watch Apple’s big announcement tomorrow